Case Report

November 2019, 26:4

First online: 21 November 2019

Case Report

Complex Congenital Heart Disease: A Rare Case of Situs Inversus with Isolated Levocardia

Aaron Ong HJ,1 SMY Toh,2 TJ Muhammad,3 MN Norazrulrizal,1 KK Sia4

2 Paediatrician, Department of Paediatric Cardiology, Penang General Hospital, Penang, Ministry of Health, Malaysia

3 Paediatric Cardiologist, Department of Paediatric Cardiology, Penang General Hospital, Penang, Ministry of Health, Malaysia

4 Consultant Gastroenterologist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Tuanku Fauziah, Perlis, Ministry of Health, Malaysia

ABSTRACT

A 22-year-old woman with underlying complex cyanotic congenital heart disease was admitted for hyperviscosity syndrome with superimposed pneumonia. She had undergone right-sided modified Blalock-Taussig shunt surgery at the age of 2 but was subsequently lost to follow-up. Further investigations found she has situs inversus with levocardia (left-sided cardiac apex), a rare condition with reported incidence of 1:22,000 in the general population. She was treated with intravenous antibiotics and had therapeutic venesection, recovering back to baseline condition. This case report highlights a rare case of situs inversus with levocardia and concomitant cyanotic congenital heart disease. With the advancement in the field of paediatric cardiology, there will be an increase in adult survivors with complex congenital heart disease. Potential long term complications should be anticipated and treated accordingly.

KEYWORDS

situs inversus, levocardia, congenital heart disease, hyperviscosity syndrome, venesection

BACKGROUND

Situs inversus with isolated levocardia (left-sided cardiac apex) is rare and is almost always associated with severe congenital heart disease (CHD) with guarded prognosis.[1] It has a reported incidence of 1:22,000 in the general population and accounts for 0.4-1.2% of all CHDs.[1, 2] The prognosis is poor, with 5 year survival rate of 5-13% from birth.[1] We report one such case with concomitant complex cyanotic CHD, living into adulthood.

CASE REPORT

A 22-year-old woman presented to a Malaysian public hospital emergency department for worsening dyspnoea, two week history of cough and fever. She was known to have complex CHD (common atrium, univentricular heart, transposed great arteries (TGA) and pulmonary atresia) and had undergone right-sided modified Blalock-Taussig shunt surgery at the age of 2. The intent of the surgery was palliative. She was then planned for further surgical intervention, however was lost to follow-up. There were no family history of heart disease or known teratogenic drug consumption by the mother during pregnancy. She was independent in all her activities of daily living (ADL) and had a baseline New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II-III. She was not on domiciliary oxygen therapy.

Upon arrival, she was evidently cyanosed with oxygen saturation of 64% under room air, was tachypnoeic at a rate of 42 breaths/min and hypotensive. She had both central and peripheral cyanosis, with grade 3 digital clubbing.

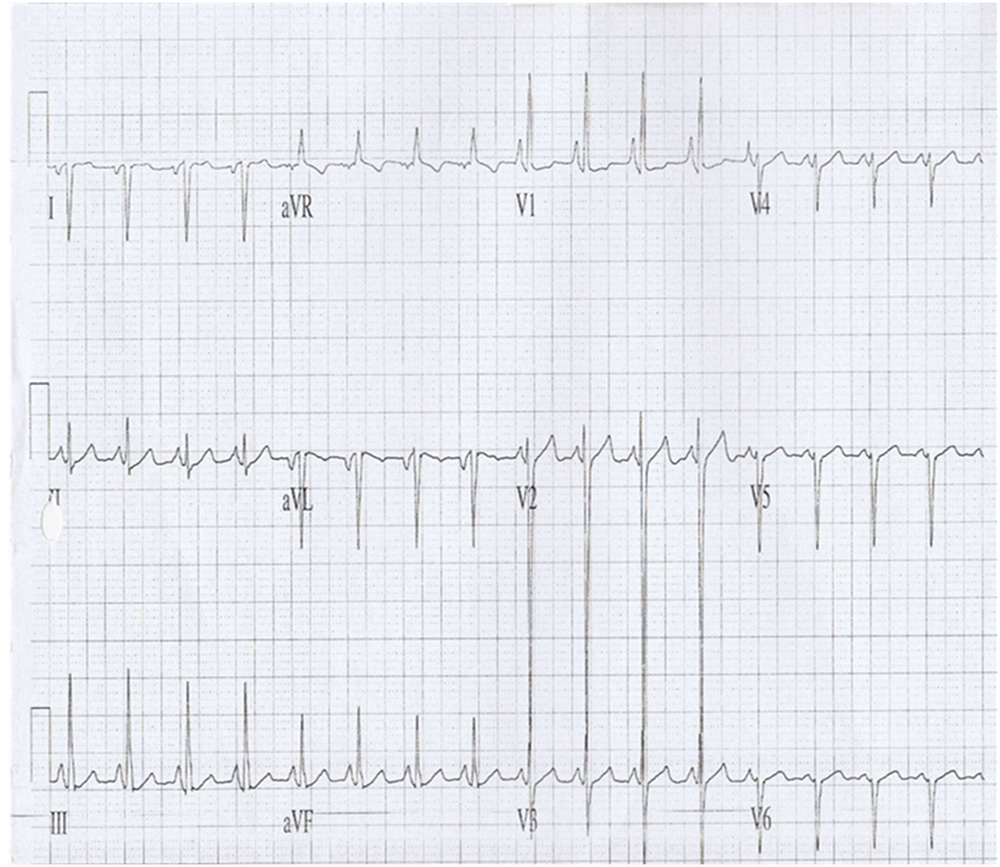

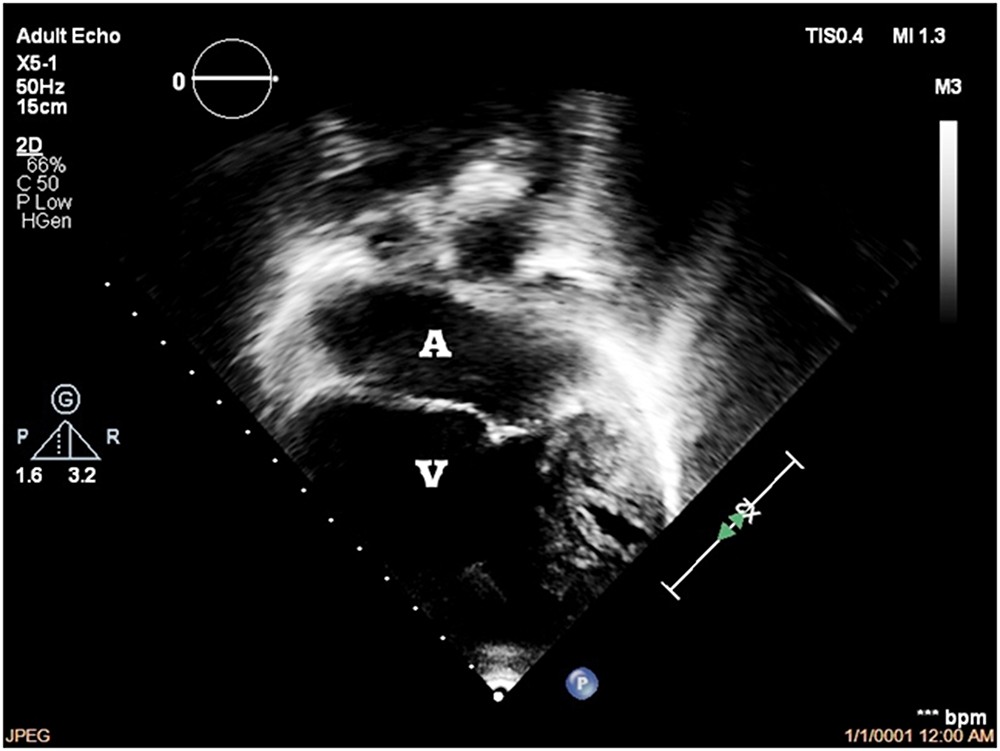

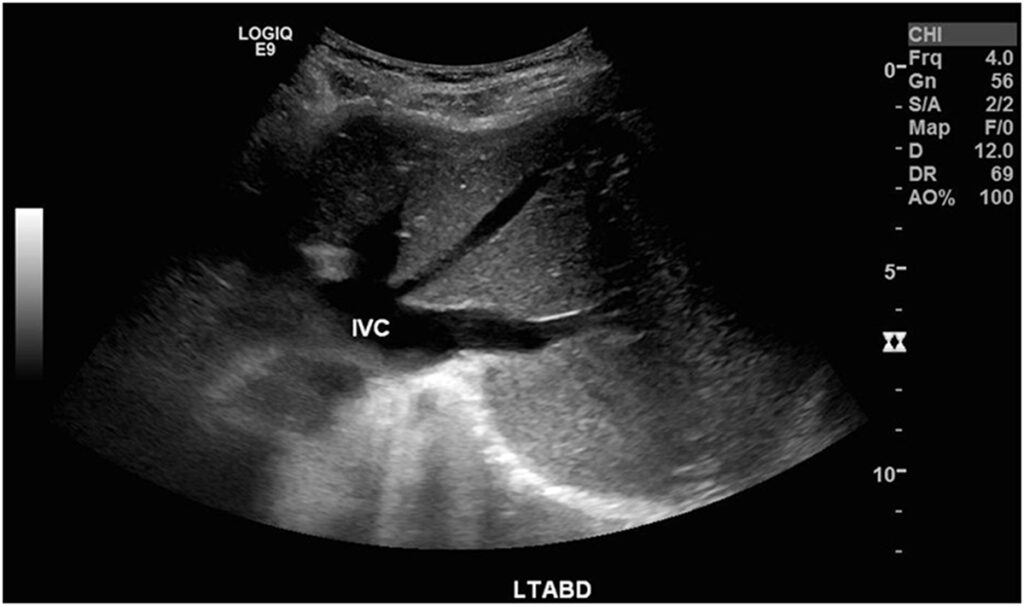

Cardiac examination revealed apex beat at the fifth intercostal space, lateral to the left sternum. She had two heart sounds with a loud second heart sound. There were crepitations over the right lung base. Abdominal examination did not reveal any mass, organomegaly or ascites. There were no pedal oedema. Investigations done demonstrated haemoglobin 23.1 x 103/μL, haematocrit 71% and arterial blood gas on room air showed partial pressure oxygen 35.9mmHg and partial pressure carbon dioxide 24.2mmHg. Subsequent workup with electrocardiogram (Fig. 1), chest X-ray (Fig. 2), echocardiogram (Fig. 3) and abdominal ultrasound (Fig. 5) revealed the diagnosis of situs inversus with levocardia and complex cyanotic CHD.

She had developed hyperviscosity syndrome as a consequence of secondary polycythaemia precipitated by superimposed pneumonia and dehydration. She was admitted to the coronary care unit (CCU) for critical care and close monitoring. High flow supplemental oxygen was given to alleviate dyspnoea and to improve oxygen saturation. There was no targeted oxygen saturation level in view her baseline oxygenation was not known.

Invasive ventilation was not required during her stay. Inotropic support was required initially, which was gradually tapered off. Intravenous Ceftriaxone was administered to treat the pneumonia. Her plasma hyperviscosity was treated with fluid hydration and therapeutic venesection by removing 400cc of blood. Her condition subsequently improved back to baseline. On discharge, her oxygen saturation on room air was >70%, with haemoglobin 19.9x 103/μL and haematocrit of 60%.

Figure 1

12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) shows inverted p-wave in leads I, aVL. Predominantly right axis deviation pattern with upright QRS complexes in aVR. This is suggestive of cardiac atrial situs inversus

Figure2

Erect chest X-ray demonstrates levocardia (left-sided heart) with left-sided aortic arch, right-sided gastric fundal bubble and scoliosis

Figure 3

Echocardiography shows situs inversus, levocardia, common atrium [A], univentricular heart (left ventricular morphology) [V], tricuspid atresia with hypoplastic right ventricle, TGA relationship of great vessels, left aortic arch with presence of major aortopulmonary collaterals (MAPCAs)

Figure 4

Schematic diagram demonstrates the cardiac blood circulation. Blue denotes deoxygenated blood, red denotes oxygenated blood and purple denotes mixed blood oxygenation

Figure 5(a)

Ultrasound of right hypochondrium shows the presence of a spleen. No evidence of polysplenism

Figure 5(b)

Ultrasound of left hypochondrium demonstrates the presence of liver. The IVC is located to the left of the aorta

DISCUSSION

Situs describes the position of the cardiac atria and abdominal viscera relative to midline. Situs solitus is the normal position while situs inversus refers to mirror-image placement of those organs. Situs inversus is almost always associated with dextrocardia (right-sided apex beat) and is linked to a 3-5% incidence of CHD. Situs inversus with levocardia (left-sided apex beat) is rare and almost always associated with CHD.1, 2 The cause, however, is not fully known.3, 4

In this case, the diagnosis of situs inversus with levocardia was made clinically and based upon a set of imaging done. The erect chest X-ray clearly demonstrated the opposing orientation of the cardiac apex towards the left and the gastric fundal bubble to the right. An abdominal ultrasound revealed the placement of the liver in the left hypochondrium while that of the spleen in the right hypochondrium. The electrocardiogram and echocardiogram done further suggests cardiac situs inversus. A cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or cardiac computed tomography (CT) scan may be useful to further delineate the cardiac anatomy.

Cyanotic CHD is associated with secondary polycythaemia. This is a physiological response to tissue hypoxia, stimulating erythropoietin production and subsequent erythropoiesis.5 It results in improved oxygen carrying capacity. However, this is offset by an increase in serum viscosity that impairs blood flow and tissue perfusion. In the setting of background cyanotic heart disease, the body regulates the degree of erythropoiesis to balance the detrimental effect of increased blood viscosity in order to optimise tissue oxygen perfusion and delivery. However, this balance can be tipped off in the presence of infection, dehydration, or failure of compensatory mechanisms, leading to hyperviscosity syndrome. Hyperviscosity syndrome may manifests as headache, visual disturbance, dyspnoea, angina, paraesthesia, lethargy or thrombosis.

This patient had developed symptomatic hyperviscosity syndrome precipitated by pneumonia and dehydration. The treatment is intravenous hydration and venesection, which results in reduced red cell mass and peripheral vascular resistance. This improves blood flow and tissue oxygen delivery.

Currently there are no studies recommending routine venesection as a long term treatment of polycythaemia in patients with cyanotic CHD. Regular venesection results in iron deficiency, leading to the production of microcytic red cells that are more viscous than normocytic red cells, paradoxically increasing the risk of thrombosis.6 These microcytic red cells are more rigid and less malleable in the microcirculation.6 Therefore, venesection is recommended only in the setting of acute hyperviscosity to avoid chronic iron deficiency.

Contemporary advances in medical care has resulted in increasing number of patients with CHD entering adulthood. Nevertheless, mortality is this patient sub group is still higher compared to the general population. The primary cause of death in adults with complex CHD remains cardiac origin, of which progressive heart failure (27%) and sudden cardiac death (23%) are the leading causes.7, 8 Extracardiac complications such as malignancy and infections are also more prevalent in this group. Pneumonia has been identified as a second leading cause of death after cardiac causes in a population study. This is postulated to be related to the associated genetic abnormality, immune system compromise or congenital lung anomaly.9 Some CHD patients with heterotaxy syndrome (abnormal arrangement of internal organs) have absence or hypofunctioning spleen, rendering them susceptible to infection with encapsulated bacteria.

CONCLUSION

This case report highlights a rare case of situs inversus with levocardia and concomitant cyanotic CHD. With the advancement in the field of paediatric cardiology, there will be an increase in adult survivors with complex CHD. Potential long term complications should be anticipated and treated accordingly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare

FUNDING

This study did not receive external funding

REFERENCES

1. Vijayakumar V, Brandt T. Prolonged survival with isolated levocardia and situs inversus. Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58:243–7. CrossRef Pubmed

2. Mujo T, Finnegan T, Joshi J et al. Situs ambiguous, levocardia, right sided stomach, obstructing duodenal web, and intestinal nonrotation: a case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2015 Feb. 9 (2):16-23. CrossRef Pubmed

3. Winer-Muram HT, Tonkin IL. The spectrum of heterotaxic syndromes. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989;27:1147–70. Pubmed

4. Jo DS, Jung SS, Joo CU. A case of unusual visceral heterotaxy syndrome with isolated levocardia. Korean Circ J. 2013;43:705–9. CrossRef Pubmed

5. Territo MC, Rosove MH. Cyanotic congenital heart disease: hematologic management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18(2):320–2. CrossRef Pubmed

6. Rose SS, Shah AA, Hoover DR et al. Cyanotic Congenital Heart Disease (CCHD) with Symptomatic Erythrocytosis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(12):1775-1777. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0356-4 CrossRef Pubmed

7. Engelings CC, Helms PC et al. Cause of death in adults with congenital heart disease – An analysis of the German National Register for congenital heart defects. Int J Cardiol. 2016 May 15;211:31-6. CrossRef Pubmed

8. Mei-Hwan W, Chun-Wei L. Adult congenital heart disease in a nationwide population 2000-2014: Epidemiological trends, arrhythmia and standardised mortality. JAHA. 2018;7:e007907 CrossRef Pubmed

9. Raissadati A, Nieminen H, Haukka J, Sairanen H, Jokinen E. Late causes of death after pediatric cardiac surgery: a 60-year population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.038. CrossRef Pubmed

Copyright Information