Case Report

December 2025, 34:3

First online: 15 December 2025

Case Report

Atrial Myxoma Presenting with Young-Onset Stroke and Late Post-Stroke Epilepsy

Shan Kai ING, M.D.,1 Benjamin Han Sim NG, M.D.,2 Yih Hoong LEE, M.D.,1 Jennie Geok Lim TAN, M.D.,3 Zheng Hong CHOW, M.D.,4 Cheng Foong CHEAH, M.D.,5 Sing Yang SOON, M.D 6

2 Division of Neurology, Department of Medicine, Sibu General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia.

3 Department of Radiology, Sibu General Hospital, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia.

4 Department of Pathology, Sarawak General Hospital, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

5 Department of Cardiology, Sarawak Heart Centre, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

6 Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Sarawak Heart Centre, Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

Main and Corresponding Author:

Dr Ing Shan Kai, Department of Medicine, Sibu General Hospital, Batu 5 ½, Jalan Ulu Oya, 96000, Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia. Tel: +6084-343333; Fax: +6084-337354; Email: shankai1992@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUNDAtrial myxoma, the most common benign cardiac tumour, may present with neurological complications, including ischaemic stroke in young adults. The optimal timing of surgical resection after stroke and the risk of subsequent post-stroke epilepsy remain unresolved clinical challenges.

CASE SUMMARYAn 18-year-old man presented with acute aphasia, right hemiplegia, and seizure. Brain imaging showed a large left middle cerebral artery infarct with ipsilateral carotid occlusion. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a left atrial myxoma. Surgery was deferred for three months due to the extensive infarct and high haemorrhagic risk. Elective resection confirmed atrial myxoma. Seven months later, the patient developed late-onset post-stroke epilepsy secondary to cortical encephalomalacia, well controlled on levetiracetam.

DISCUSSIONThis case highlights the diagnostic importance of echocardiography in young-onset stroke, the balance between early and delayed cardiac surgery following cerebral infarction, and the need for long-term neurological follow-up after curative resection.

KeywordsAtrial myxoma, cardioembolic stroke, surgical timing, post-stroke epilepsy, young stroke

INTRODUCTION

Atrial myxoma, though rare, represents a critical cardiac source of embolic stroke, particularly in young adults. Despite an annual incidence of 0.5 per million, it remains the most frequent primary cardiac tumour associated with neurological events.¹ Neurological manifestations occur in up to 30% of cases, often as large-vessel embolic infarcts.²

Although surgical resection is curative, its optimal timing after stroke remains contentious. Early surgery mitigates recurrent embolic events but increases the risk of haemorrhagic transformation, particularly in large infarcts.³ Additionally, poststroke epilepsy (PSE) may occur months later in patients with cortical injury or encephalomalacia.4 This report illustrates the multidisciplinary considerations in managing atrial myxoma presenting with stroke and subsequent epilepsy.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old right-handed man, previously healthy apart from a 5-pack-year smoking history, presented with sudden-onset aphasia and right hemiplegia. The onset was preceded by tonic stiffening of all limbs with drooling, lasting one minute, followed by post-ictal unresponsiveness. On admission, he was drowsy but arousable (GCS E3V1M6) with dense right hemiplegia, Wernicke’s aphasia, neglect, and an NIHSS score of 22.

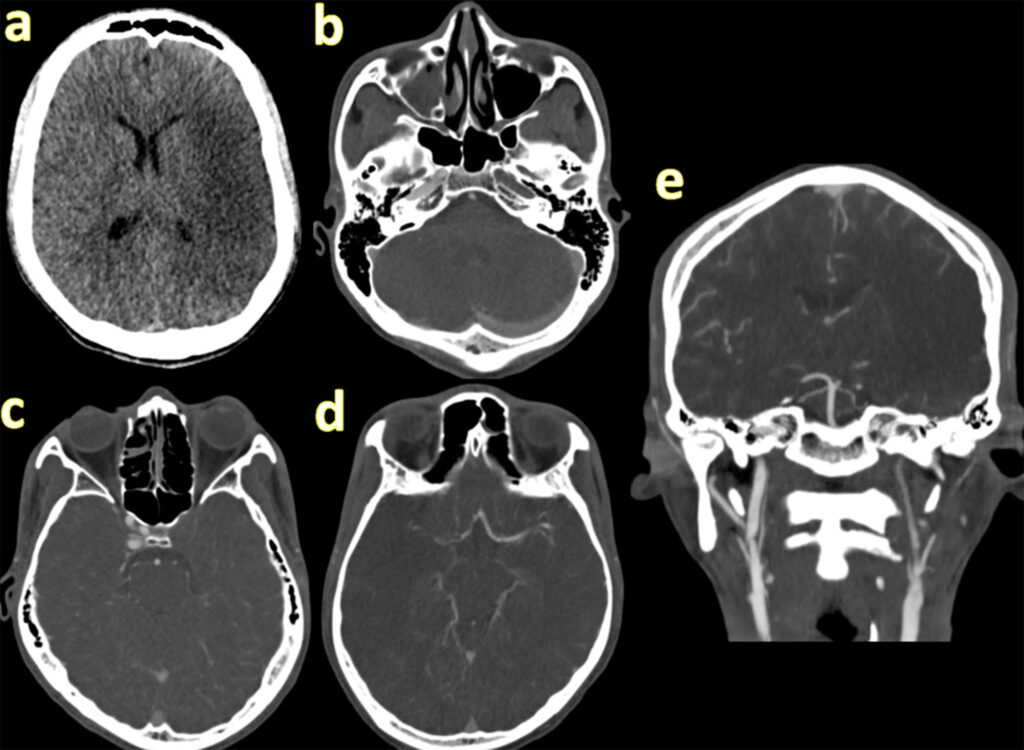

Non-contrast CT brain excluded haemorrhage. CT angiography revealed a large left MCA/ACA infarct with occlusion of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery (Figure 1). ECG showed sinus rhythm and baseline blood tests were unremarkable. He presented outside the thrombolysis window, and mechanical thrombectomy was unavailable locally.

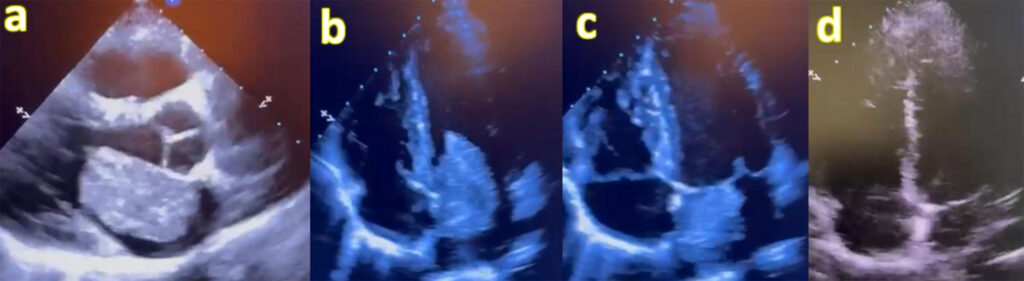

Bedside transthoracic echocardiography revealed a pedunculated, friable mass measuring 4 × 4.5 cm attached to the interatrial septum, intermittently obstructing mitral inflow, consistent with left atrial myxoma (Figure 2).

Owing to the extensive infarct and high risk of haemorrhagic transformation, urgent surgery was deferred. He received multidisciplinary rehabilitation with gradual improvement in comprehension but persistent motor deficits. Antiepileptic therapy was discontinued after two weeks as no further seizures occurred.

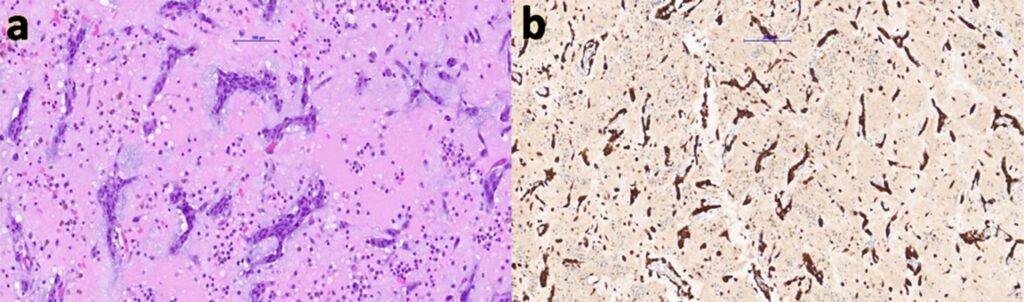

Three months later, elective resection of the atrial mass was performed. Intraoperatively, a friable tumour was excised completely, and histopathology confirmed atrial myxoma (Figure 3). Postoperative echocardiography showed preserved function with no residual mass.

Seven months after the index stroke, the patient re-presented with recurrent seizures, initially focal motor jerks of the right upper limb progressing to generalised tonic–clonic seizures. CT brain showed encephalomalacia of the left fronto-parietotemporal cortex with ex vacuo dilatation of the lateral ventricle (Figure 4). He was commenced on levetiracetam 1 g twice daily with good seizure control.

The final diagnosis was cardioembolic stroke secondary to atrial myxoma, complicated by late-onset post-stroke epilepsy.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights several cardiological and neurological intersections. Cardiac sources, particularly atrial myxoma, should be actively sought in young-onset ischaemic stroke. Early echocardiography—transthoracic or transoesophageal— is crucial to prevent missed diagnoses and recurrent embolic events.2

We performed a PubMed search using the terms “atrial myxoma AND stroke”, “cardiac tumor embolic stroke”, and “atrial myxoma AND epilepsy” from database inception to August 2025, limited to human studies and English language. This search yielded 391 published articles. Reports of atrial myxoma causing stroke are well documented, but late-onset post-stroke epilepsy following curative resection remains extremely rare, reported in fewer than 5% of cases.

The timing of resection after stroke must balance embolic recurrence risk against perioperative haemorrhagic transformation. Emerging data suggest early surgery (≤30 days) may be safe in moderate infarcts, but extensive infarction (as in this case) warrants a delayed approach to avoid catastrophic bleeding.3, 5, 6 In our case, the extensive infarct burden (NIHSS 22) rendered early surgery hazardous, justifying the three-month delay. Nevertheless, the risk of embolisation during this period underscores the urgent need for tailored, multidisciplinary decision-making between cardiology, neurology, and cardiothoracic surgery.

Among the 391 indexed cases, most involved patients aged 30–60 years, with mean age 45 years.7, 8 Our patient was only 18 years old—among the youngest reported with combined large hemispheric infarct, delayed resection, and late poststroke epilepsy. Reports of post-stroke seizures secondary to atrial myxoma emboli are exceedingly scarce, and even fewer document late epilepsy months after surgery.9, 10

PSE occurs in 6–15% of stroke survivors, with cortical involvement and encephalomalacia being major risk factors.4, 11, 12 In this case, seizures developed several months after surgery, reinforcing the need for ongoing neurological surveillance even when the embolic source has been eliminated. Levetiracetam provided excellent seizure control, consistent with current firstline recommendations.13, 14

This case therefore emphasises the interplay between cardiovascular pathology, neurological complications, and the importance of long-term follow-up. It also highlights the educational value of a multidisciplinary approach involving neurology, cardiology, cardiothoracic surgery, pathology, and rehabilitation medicine.

This report is distinct for (1) the extremely young age of onset (18 years), (2) massive hemispheric infarction with high NIHSS, (3) delayed but successful curative resection, and (4) late poststroke epilepsy — an exceptionally rare sequence not previously reported from Southeast Asia.

CONCLUSION

Atrial myxoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of young-onset ischaemic stroke. Early echocardiography facilitates timely diagnosis, while the timing of surgical excision must balance recurrent embolic risk with perioperative neurological complications. Even after successful tumour resection, patients remain at risk for long-term sequelae such as post-stroke epilepsy, underscoring the importance of vigilant follow-up and comprehensive multidisciplinary care.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

- Not applicable

Consent for Publication

- Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Availability of Data and Material

- Not applicable

Competing Interests

- The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

- The authors declare that no funding was received for the publication of this case report.

Authors’ Contributions

- SKI conceived the idea for case reporting and prepared the final manuscript with YHL. BHSN is the managing neurologist. CFC is the managing cardiologist. SYS is the managing cardiothoracic surgeon. JGLT interpreted all imaging studies. ZHC is the pathologist analysing all the histopathology specimens. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

- None declared

Acknowledgement

- The authors would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for the permission to publish this paper.

REFERENCES

1. Kesav P, Chaturvedi S, Kumar S, et al. Cardiac myxoma embolization causing ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2021;52(1):e1–e4. CrossRef Pubmed

2. Sohal RS, Shergill KK, Nagi GS, Pillai HJ. Atrial myxoma – an unusual cause of ischemic stroke in young. Autops Case Rep. 2020;10(4):e2020178. CrossRef Pubmed

3. Tu X, Tan H, Song Q, et al. Early and intermediate outcomes of surgical treatment for left atrial myxoma complicated by preoperative ischaemic stroke. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30:569. CrossRef Pubmed

4. Tanaka T, et al. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, prognosis, and prevention of post-stroke epilepsy. Neurology. 2024;103(5):245–53.

5. Lee VH, Connolly HM, Brown RD Jr. Central nervous system manifestations of cardiac myxoma. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(8):1115–20. CrossRef Pubmed

6. Yuan SM. Cardiac myxoma: clinical features, diagnosis and treatment. J Card Surg. 2015;30(2):91–5.

7. Bhattacharyya S, Khattar RS, Senior R. Atrial myxoma: a review. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2021;22(8):1149–59.

8. Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac myxoma: a series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80(3):159–72. CrossRef Pubmed

9. Nakamura K, et al. Recurrent seizures after cardioembolic stroke from atrial myxoma: a case report. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2022;18:100535.

10. Ohtani R, et al. Late-onset epilepsy following left atrial myxoma–related embolic stroke. Intern Med. 2023;62(14):2087–90.

11. Feyissa AM, Hasan TF, Meschia JF. Stroke-related epilepsy. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):18–e3. CrossRef Pubmed

12. Galovic M, et al. Predictors of late seizures after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1272–e1284.

13. Beghi E, et al. Levetiracetam in the treatment of post-stroke epilepsy: evidence and guidelines. CNS Drugs. 2023;37(1):77–88.

14. Gaspard N, et al. Management of epilepsy after stroke: a practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2024;24(1):35–44.

Copyright Information