Original Article

December 2025, 34:3

First online: 15 December 2025

Original Article

Predictors of Mortality by Various Parameters in Cardiac ICU Patients: A Prospective Study

Devrath Parmar,1 Kamal Sharma,2 Maulik Kalyani,3 Dixit Dhorajiya,3 Arjun Lal3

2 Associate Professor, Department of Cardiology; U. N. Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre (UNMICRC), Civil Hospital Campus, Asarwa, Ahmedabad-380016, Gujarat, India

3 DM Resident, Department of Cardiology; U. N. Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre (UNMICRC), Civil Hospital Campus, Asarwa, Ahmedabad-380016, Gujarat, India

Main author for correspondence:

Dr Kamal Sharma, Associate Professor, Department of Cardiology,

Email: kamalcardiodoc@gmail.com, M: 91- 9426020154, Fax: 079-22682092

UNMICRC, Civil Hospital Campus, Asarwa, Ahmedabad-380016, Gujarat, India.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUNDVenous blood gas oxygen (VBGO2%) is a critical tool for assessing cardiac patients admitted to the ICCU. This study aimed to evaluate the association of VBGO2% and other clinical parameters with in-hospital all-cause mortality.

METHODS

This prospective, open label study included 385 consecutive patients with primarily cardiac diseases admitted to the ICCU. Apart from demographics and hemodynamics; VBGO2%, venous lactate, hydrogen carbonate (HCO3), cardiac output, and cardiac index were measured. A VBGO2% cut-off for mortality was determined using ROC curve analysis. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association of low VBGO2% with clinical variables.

RESULTS

Among 385 patients, 341(88.57%) were survivors and 44 (11.43%) were non-survivors. Demographic, laboratory, and clinical variables were distributed similarly between the two groups. However, non-survivors had significantly lower VBGO2% (0.27±0.08) compared to survivors (0.4±0.12, P < 0.0001). Nonsurvivors also had significantly higher lactate levels (6.56±3.52) and lower HCO3 and mixed venous oxygen saturation SvO2 levels. ROC curve analysis identified a VBGO2% threshold of <0.4 as predictor of mortality. Logistic regression revealed that lower SBP, higher VBG lactate, lower HCO3, and lower SVR were significant predictors of reduced VBGO2%.

CONCLUSION

While SvO2 mixed venous oxygen saturation, measured through pulmonary artery catheterization remains the gold standard, VBGO2% is a less invasive and potential alternative that correlates well with SvO2 trends. A lower VBGO2% is strongly associated with mortality, making it a valuable tool for predicting outcomes, especially in resource-limited settings. Continuous monitoring of VBGO2% could enhance clinical decision-making, allowing early identification of high-risk patients and guiding timely interventions to improve outcomes.

Keywords

Venous oxygen saturation (VBGO2%), Cardiac index, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, pulmonary artery catheterization, mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2), systemic vascular resistance (SVR)

1. BACKGROUND

Venous oxygen saturation has been a key focus of clinical research for over 50 years, with significant advancements in understanding its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications in critically ill patients, particularly those with cardiac disease. Studies have shown that SvO2 levels are markedly reduced in patients with cardiogenic shock or left ventricular failure, reflecting the inability of the failing heart to adequately increase cardiac output (CO) during periods of elevated oxygen demand. In such cases, the body’s only compensatory mechanism is increased oxygen extraction, leading to inverse changes in venous oxygen saturation.1, 2 A decline in SvO2 serves as a sensitive marker of cardiac deterioration and may indicate the presence of shock in the early stages of disease progression.3, 4, 5

In septic patients with preexisting left ventricular dysfunction, early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) based on SvO2 monitoring has been associated with improved outcomes, as recommended by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines. Similarly, in the context of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, a central venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) value of ≥72% is highly predictive of the return of spontaneous circulation, emphasizing its value in guiding therapeutic interventions.3, 4, 5

Continuous monitoring of SvO2 has also demonstrated prognostic significance, as frequent short-term fluctuations in SvO2 are observed more often in non-survivors of septic shock. (6) Low SvO2 values have been linked to increased complications and morbidity, particularly in perioperative care and cardiac surgery. The use of SvO2 targets >70% appears promising, especially during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and in the perioperative management of high-risk surgical patients.6 However, despite these insights, the lack of standardized therapeutic guidelines and concerns about cost-effectiveness remains a challenge to its broader clinical application.7, 8, 9 Over the past decade, there has been a substantial increase in literature exploring changes in ScvO2 and SvO2 in critically ill and high-risk surgical patients. This growing body of evidence underscores the importance of venous oxygen saturation monitoring in optimizing outcomes across a range of clinical settings.

Our study aimed to evaluate VBGO2 as the predictor of mortality and different factors associated with venous blood saturation in ICU patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHOD

The present prospective observational study enrolled total 385 patients who presented cardiogenic shock, heart failure and acute coronary syndrome at largest tertiary care Institute of cardiology and research in India from June 2021 to May 2022. Demographic and clinical information were captured of all the patients after informed consent was obtained to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria

All the eligible ICCU hospitalised patients between 18-80 years of age who consented were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 or older than 80 years of age; Patient having any detectable shunt lesion, had a serious tachyarrhythmia or Bradyarrhythmias at the time of sample collection, Severe septic shock, severe anaemia, thyrotoxicosis, A-V fistula or Brain-dead were also excluded.

Protocol:

In our study all patients were treated according to standard treatment. Here we have tried to correlate various parameters in the patient admitted to ICCU and help determine the prognosis of sick patients admitted in ICCU. The patient’s present and previous cardiac history was obtained. The patient’s weight and height recorded. Body surface area was calculated based BSA = (W 0.425 x H 0.725) x 0.007184.

- Baseline vital parameters recorded were Heart Rate, SBP, DBP, SpO2.

- Systemic examination was done and based on history and examination.

- Baseline Killip and/or NYHA class were noted.

- According to the Fick principle10, SvO2 can be described by the following formula: SvO2 = [SaO2 – VO2 / CO] [1 / Hb × 1.34]

The study was approved by the ethics committee (UNMICRC/ CARDIO/2021/06).

Statistical analysis:

All statistical studies were carried out using the SPSS program vs 20. Quantitative variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and qualitative variables were expressed as number (%). A comparison of parametric values between two groups was performed using the independent sample t-test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. The predictive diagnostic value of venous saturation (VBG) for mortality was calculated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Logistic regression was used to predict the variables for venous saturation during ICU stay. A nominal statistical significance was indicated by two tailed P-value ≤0.05 for all analyses carried out in this investigation.

3. RESULTS

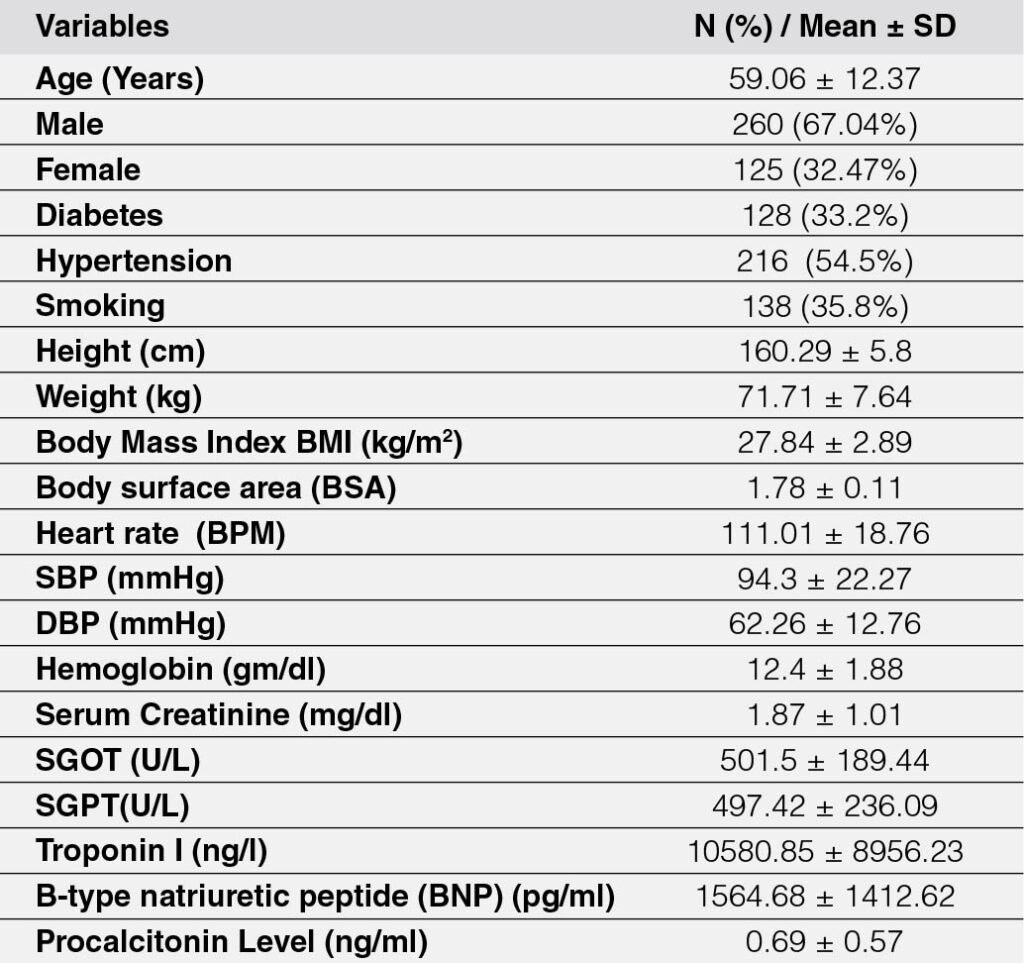

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1: The mean age was 59.06 ± 12.37 years, with a predominance of males (67.04%). Comorbidities included diabetes in 33.2% and hypertension in 54.5%, while 35.8% of participants were tobacco smokers. The mean body mass index (BMI) was 27.84 ± 2.89 kg/m², and the average body surface area (BSA) was 1.78 ± 0.11 m². Participants had a mean heart rate of 111.01 ± 18.76 bpm, systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 94.3 ± 22.27 mmHg, and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 62.26 ± 12.76 mmHg.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the population

Laboratory parameters revealed a mean haemoglobin level of 12.4 ± 1.88 g/dL and serum creatinine of 1.87 ± 1.01 mg/dL. Liver enzymes SGOT and SGPT were markedly elevated at 501.5 ± 189.44 U/L and 497.42 ± 236.09 U/L, respectively. Troponin I levels averaged 10,580.85 ± 8,956.23 ng/L, indicating significant underlying cardiac injury. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) was elevated at 1,564.68 ± 1,412.62 pg/mL, and Procalcitonin levels were 0.69 ± 0.57 ng/mL. These data highlight the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and organ dysfunction in the study cohort.

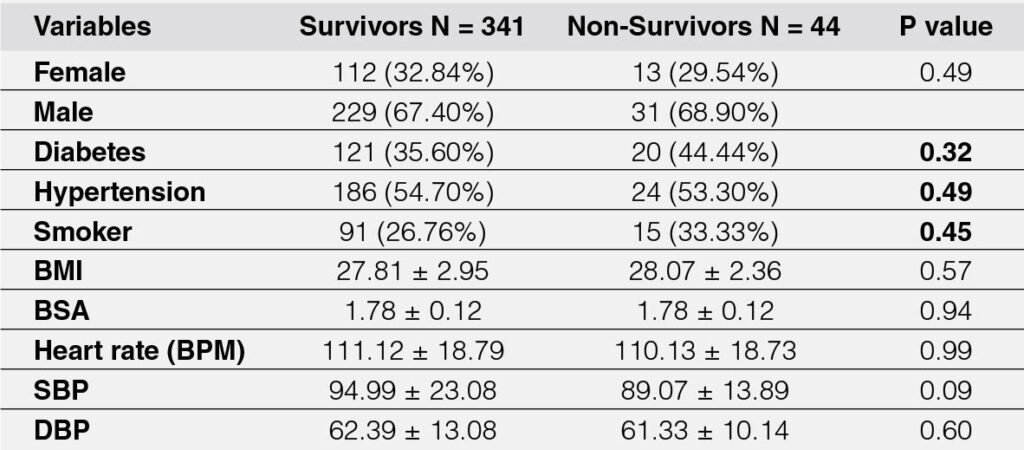

The study included 341 survivors and 44 non-survivors, and the baseline characteristics of the two groups were compared (Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in sex distribution, with 32.84% of survivors being female compared to 29.54% of non-survivors (P = 0.49). Similarly, the proportion of males was comparable (67.40% vs. 68.90%). Diabetes was slightly more prevalent among non-survivors (44.44%) compared to survivors (35.60%), but the difference was not significant (P = 0.32). Hypertension was observed in 54.70% of survivors and 53.30% of non-survivors, while smoking prevalence was higher among non-survivors (33.33%) than survivors (26.76%), with neither reaching statistical significance (P = 0.49 and P = 0.45, respectively). Body Mass Index (BMI) and Body Surface Area (BSA) were also similar between the groups. Both groups had an identical mean BSA of 1.78 ± 0.12 (P = 0.94). The mean heart rate was nearly identical, with 111.12 ± 18.79 BPM in survivors and 110.13 ± 18.73 BPM in non-survivors (P = 0.99). While systolic blood pressure (SBP) was slightly higher in survivors (94.99 ± 23.08 mmHg) than in non-survivors (89.07 ± 13.89 mmHg), this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.09). Similarly, the diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was comparable between the groups, with survivors having a mean DBP of 62.39 ± 13.08 mmHg and non-survivors 61.33 ± 10.14 mmHg (P = 0.60). Overall, no statistically significant differences were observed between survivors and non-survivors in these analysed variables.

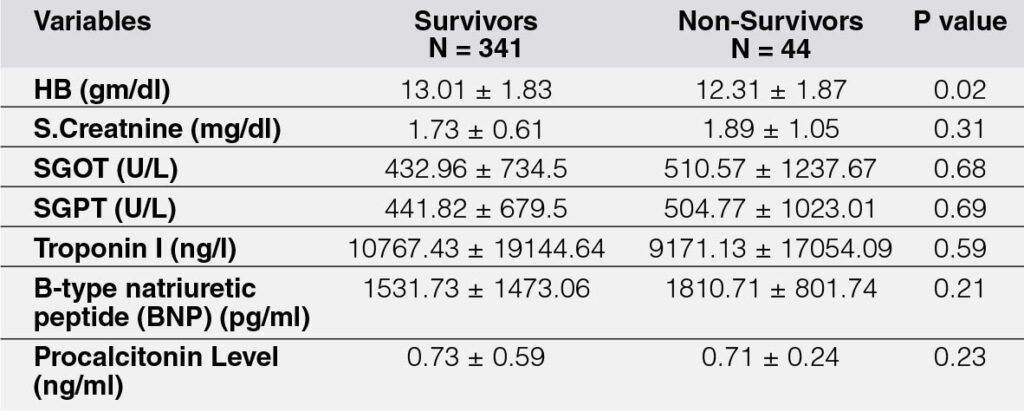

Non-survivors had significantly lower hemoglobin levels (13.01 ± 1.83 vs. 12.31 ± 1.87 gm/dl, P = 0.02). Other parameters, including serum creatinine, liver enzymes (SGOT, SGPT), Troponin I, BNP, and pro-calcitonin levels, showed no statistically significant differences between the groups (Table 3).

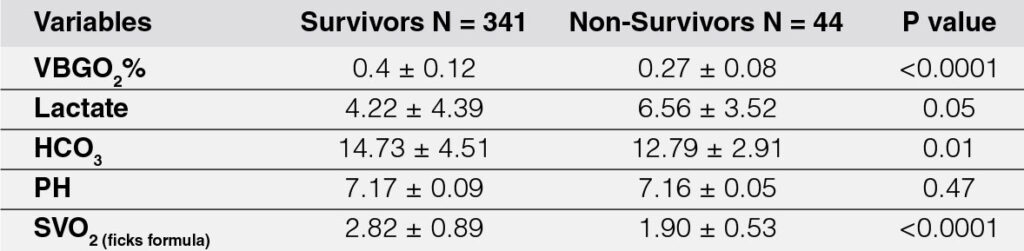

The analysis of blood gas parameters revealed significant differences between survivors (N = 341) and non-survivors (N = 44) mentioned in Table 4. Venous blood gas oxygen saturation (VBGO2%) was significantly higher in survivors (0.40 ± 0.12) compared to non-survivors (0.27 ± 0.08, P < 0.0001). Lactate levels were elevated in non-survivors (6.56 ± 3.52) compared to survivors (4.22 ± 4.39), with borderline statistical significance (P = 0.05). Bicarbonate (HCO3) levels were significantly lower in non-survivors (12.79 ± 2.91) compared to survivors (14.73 ± 4.51, P = 0.01). However, pH levels were similar between the groups (7.17 ± 0.09 in survivors vs. 7.16 ± 0.05 in nonsurvivors, P = 0.47). Mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) calculated using Fick’s formula was significantly higher in survivors (2.82 ± 0.89) than in non-survivors (1.90 ± 0.53, P < 0.0001). These findings suggest significant differences in oxygenation and metabolic parameters between the two groups.

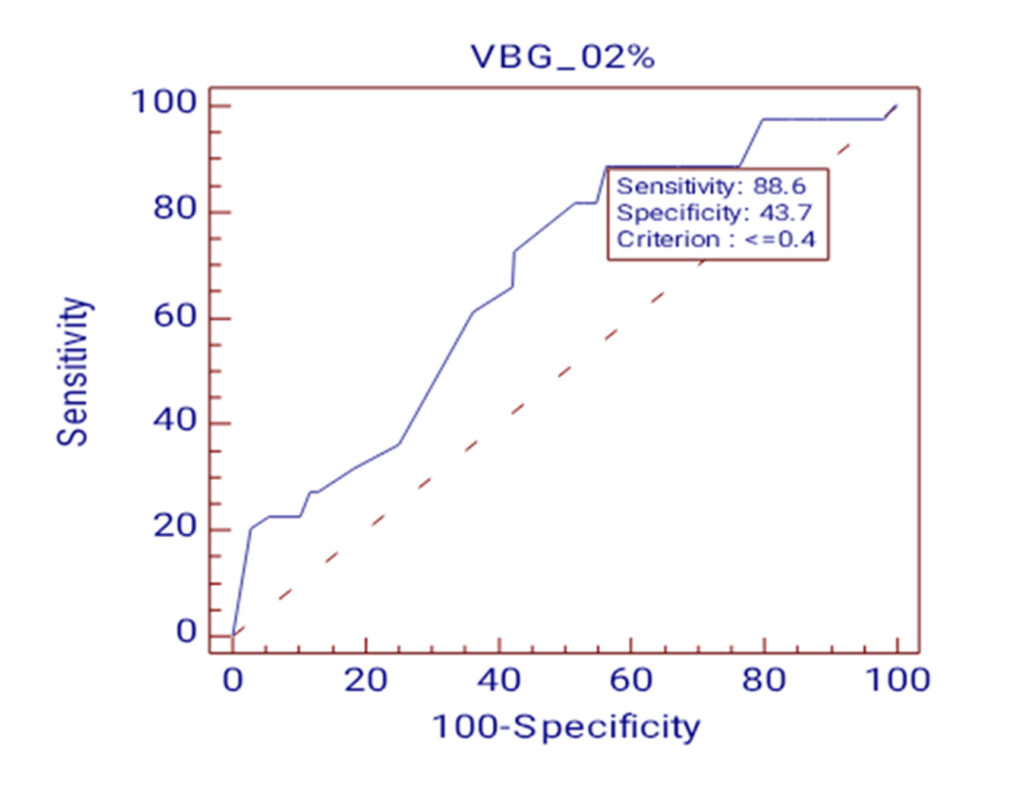

The ROC curve identified a threshold value of VBGO2% ≤ 0.4 for predicting mortality, with a sensitivity of 88.6% and specificity of 43.7%. The AUC was 0.68 (95% CI: 0.627–0.723, P < 0.0001), indicating fair predictive accuracy shown in Figure 1.

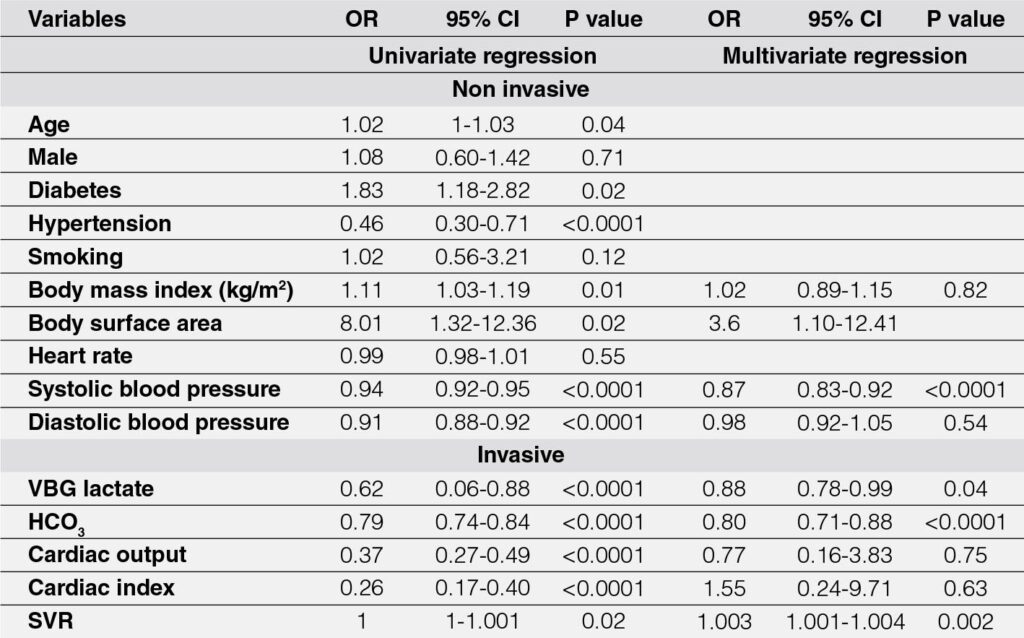

Table 5 showed the non-invasive parameters, univariate regression identified higher age (OR 1.02, 95% CI 1–1.03, P = 0.04), presence of diabetes (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.18–2.82, P = 0.02), and higher body mass index (BMI) (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03–1.19, P = 0.01) as significant positive predictors of SvO2. Conversely, hypertension (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.30–0.71, P < 0.0001), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.92–0.95, P < 0.0001), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.88–0.92, P < 0.0001) were negatively associated with SvO2. Body surface area (BSA) also showed a strong positive association (OR 8.01, 95% CI 1.32–12.36, P = 0.02). On multivariate regression, only SBP remained a significant predictor (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.83–0.92, P < 0.0001), while BMI (P = 0.82) and DBP (P = 0.54) lost significance. BSA also was found to be significant (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.10–12.41).

Among invasive parameters, univariate analysis revealed significant predictors, including venous blood gas lactate (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.06-0.88, P < 0.0001), bicarbonate (HCO3) (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.74–0.84, P < 0.0001), cardiac output (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.27–0.49, P < 0.0001), cardiac index (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.17–0.40, P < 0.0001), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) (OR 1.001, 95% CI 1–1.001, P = 0.02). On multivariate regression, significant predictors included lactate (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.78–0.99, P = 0.04), HCO3 (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71–0.88, P < 0.0001), and SVR (OR 1.003, 95% CI 1.001–1.004, P = 0.002). Cardiac output and cardiac index were no longer significant (P = 0.75 and P = 0.63, respectively).

Overall, lower SBP, lower lactate, reduced HCO3, and elevated SVR were independent predictors of venous oxygen saturation, reflecting the complex interplay of hemodynamic and metabolic factors in determining oxygen delivery and utilization.

4. DISCUSSION

In this prospective study, we aimed to identify predictors of low venous oxygen saturation in ICU patients at our institute. The study included patients with various conditions, such as ischemic heart disease (IHD), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCMP), and valvular disorders. Patients who did not survive had significantly lower VBGO2 levels compared to survivors. We identified a threshold value of <0.4% of VBGO2 for predicting mortality. Using this threshold as a binary variable, systolic blood pressure, VBG lactate, HCO3, and SVR were found to be independent predictors of low venous oxygen saturation.

Kyff et al.11 investigated continuous mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) monitoring in 24 patients with complicated myocardial infarctions. They found that increases in SvO2 correlated with increases in cardiac index in 75-78.5% of cases, while decreases in SvO2 correlated with decreases in cardiac index in 45.5-61% of cases. However, in 62% of cases with 20% hanges in cardiac index, SvO2 trends did not align, highlighting its limitations as a consistent marker of cardiac output. Additionally, arterial lactate levels showed poor correlation with SvO2. Survivors had significantly higher mean SvO2 and cardiac indices compared to non-survivors (P < 0.01). Both this study and the present study demonstrate that SvO2 is significantly lower in non-survivors, indicating impaired systemic oxygenation as a critical marker of poor prognosis. Nevertheless, these findings emphasize that SvO2 alone may not reliably reflect cardiac output or tissue hypoxia, underscoring the importance of multimodal monitoring in critically ill patients.

In our study, we observed that lower SvO2 and VBGO2 values were significantly associated with non-survivors, indicating impaired systemic oxygenation, which is consistent with previous studies.12, 13 Both parameters served as critical indicators of poor prognosis in patients, pointing to compromised oxygen delivery or increased oxygen consumption at the tissue level. It is important to note that, although these markers are closely related, VBGO2 may offer certain advantages in its ease of measurement and non-invasive nature compared to direct SvO2 monitoring. Both parameters underscore the importance of continuous monitoring to assess oxygenation and predict patient outcomes, although they may require additional clinical data to comprehensively assess the severity of disease, such as lactate levels or cardiac index. Given the similarities and differences between VBGO2 and SvO2, our findings further emphasize the need for multimodal monitoring in critically ill patients. SvO2 provides more direct and continuous data on cardiac function and tissue oxygen extraction, while VBGO2 serves as a more easily accessible marker for general systemic oxygenation.

Various studies used mixed venous blood saturation to show in hospital mortality and critical events. Here in present study we found significantly higher mortality in patients with low mixed venous blood glucose saturation. Previous study14 involving cardiac surgery patients and those from other surgical specialties have demonstrated an association between low central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) and mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) with poor clinical outcomes.

In present study we found cut-off value of less than 0.4 of the VBGO2 as the indicator of mortality. And using these cutoff value we found the predictors of lower VBGO2 value. We found SBP as the non-invasive predictor and VBG lactate, HCO3 and SVR were the invasive parameters of the lower VBGO2 in present study population.

Study by Sumimoto et al.15 reported no survivors exhibited a significant decline in oxygen delivery to tissues due to lower cardiac index and hemoglobin concentration compared to survivors. Despite this, no survivors had a higher rate of oxygen consumption at the same level of oxygen delivery, leading to a greater decrease in SvO2. This suggests that no survivors had an increased oxygen demand, which contributed to the larger drop in SvO2 levels, highlighting impaired oxygen transport and greater metabolic stress in this group. It supports the notion that SvO2 is a better predictor of survival than cardiac index, emphasizing its role in reflecting the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption. This may also be associated with increased oxygen demand and impaired oxygen transport mechanisms in critically ill patients. In present study SvO2 was significantly lower in non-survivors, which aligns with these findings. Both studies suggest that impaired systemic oxygenation (reflected in lower SvO2 levels) is a critical marker of poor prognosis. However, like in the study above, our research may highlight that SvO2 can serve as a more reliable predictor of survival compared to other parameters (e.g., cardiac index), particularly in critically ill patients.

Mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) monitoring serves as an indicator of the balance between systemic oxygen delivery and consumption in critically ill patients. Various studies have shown the central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) and in-hospital complications.

In conclusion, similar to other study findings, our study demonstrates that lower SvO2 levels in non-survivors are indicative of impaired oxygenation and are strongly associated with poor prognosis. Both studies highlight that SvO2 is a critical marker of systemic oxygen delivery and consumption, with significant decreases in SvO2 reflecting increased oxygen demand and impaired oxygen transport in critically ill patients. Despite the importance of SvO2, our results also suggest that SvO2 is a more reliable predictor of survival than other parameters, such as cardiac index, in patients with acute myocardial infarction. These findings underscore the importance of continuous SvO2 monitoring as an effective tool in guiding clinical management and predicting outcomes, although further investigation into multimodal monitoring is warranted to improve prognostication and management in this patient population. While SvO2 measured via pulmonary artery catheterization is considered the gold standard for assessing mixed venous oxygen saturation, VBGO2% (from peripheral venous blood gas) offers a less invasive and more easily accessible alternative. VBGO2% has been shown to correlate closely with SvO2 trends in various clinical scenarios, making it a practical tool for routine mortality prediction, particularly in resource-limited or emergency settings.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our study highlights the significant role of mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) as a key indicator of oxygenation and prognosis in critically ill patients, particularly those with acute myocardial infarction. Lower SvO2 levels in non-survivors were strongly associated with impaired oxygen delivery and increased oxygen demand, suggesting that SvO2 is a critical marker for predicting survival. Although SvO2 measured through pulmonary artery catheterization is the gold standard, VBGO2% provides a viable and less invasive alternative, correlating well with SvO2 trends. This makes it a practical tool for assessing mortality risk, especially in settings with limited resources.

6. IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTION

Monitoring of SvO2 or VBGO2% in ICCU patients can facilitate early detection of circulatory failure and guide timely, targeted interventions to improve survival outcomes. Specifically, a VBGO2% value ≤ 0.4 serves as an early indicator of high mortality risk, allowing prompt clinical action and better patient management.

7. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, as a single-center study, the findings may lack generalizability to other populations and healthcare settings. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between VBGO2% and mortality or other clinical parameters. Additionally, the smaller sample size of non-survivors compared to survivors may have affected the statistical power of the analysis, potentially limiting the robustness of the conclusions. The absence of continuous monitoring and the lack of inclusion of advanced hemodynamic or oxygenation parameters, such as tissue oxygen saturation, further constrain the study’s ability to capture dynamic changes and provide a more comprehensive assessment. Moreover, the heterogeneity of cardiac conditions in the study population may have introduced variability in outcomes. Elevated lactate levels, although significant in non-survivors, may reflect other conditions like sepsis or metabolic dysfunction, potentially confounding the results. Finally, while VBGO2% is practical for resource-limited settings, its findings may not fully translate to centres equipped with more advanced monitoring tools. These limitations highlight the need for further research to validate and expand upon our findings.

Ethics information

All participants provided written consent. Participation was voluntary, and participants had the right to withdraw at any time during the survey. This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and was granted by the Research Ethics Committee.

Funding

The research received no external funding or financial support.

Author contributions

Conception and design of Study: KS, DSP.

Literature review: MK, DD, AL.

Acquisition of data: AL.

Analysis and interpretation of data: KS, DSP.

Research investigation and analysis: KS, DSP.

Data collection: MK, DD, AL.

Drafting of manuscript: DD, AL, MK.

Abbreviation List

VBGO2% – Venous blood gas oxygen

HCO3 – Hydrogen carbonate

SvO2 – Mixed venous oxygen saturation

ScvO2 – Central venous oxygen saturation

EGDT – Early goal-directed therapy

VBG – Venous blood gas

ROC – Receiver operating characteristic

SBP – Systolic blood pressure

DBP – Diastolic blood pressure

BMI – Body mass index

BSA – Body Surface Area

IHD – Ischemic heart disease

ACS – Acute coronary syndrome

DCMP – Dilated cardiomyopathy

SVR – Systemic vascular resistance

Source of funding

U. N. Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre (UNMICRC), Civil Hospital Campus, Asarwa, Ahmedabad-380016, Gujarat, India

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Kan, K et al. “Relation between mixed venous blood oxygen saturation and cardiac pumping function at the acute phase of myocardial infarction.” Japanese circulation journal vol. 53,12 (1989): 1481-90. doi:10.1253/jcj.53.1481 CrossRef Pubmed

2. Ander, D S et al. “Undetected cardiogenic shock in patients with congestive heart failure presenting to the emergency department.” The American journal of cardiology vol. 82,7 (1998): 888-91. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00497-4 CrossRef Pubmed

3. Shah S, Ouellette DR. Early goal-directed therapy for sepsis in patients with preexisting left ventricular dysfunction: a retrospective comparison of outcomes based upon protocol adherence. Chest. 2010 Oct 1;138(4):897A. doi:10.1378/chest.10247 CrossRef

4. Dellinger, R Phillip et al. “Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock.” Critical care medicine vol. 32,3 (2004): 858-73. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000117317.18092.e4 CrossRef Pubmed

5. Krafft, P et al. “Mixed venous oxygen saturation in critically ill septic shock patients. The role of defined events.” Chest vol. 103,3 (1993): 900-6. doi:10.1378/chest.103.3.900 CrossRef Pubmed

6. Rivers, E P et al. “The clinical implications of continuous central venous oxygen saturation during human CPR.” Annals of emergency medicine vol. 21,9 (1992): 1094-101. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(05)80650-x CrossRef Pubmed

7. Connors, A F Jr et al. “The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators.” JAMA vol. 276,11 (1996): 889-97. doi:10.1001/jama.276.11.889 CrossRef Pubmed

8. Harvey, Sheila et al. “Assessment of the clinical effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in management of patients in intensive care (PAC-Man): a randomised controlled trial.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 366,9484 (2005): 472-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67061-4 CrossRef Pubmed

9. Kern, Jack W, and William C Shoemaker. “Meta-analysis of hemodynamic optimization in high-risk patients.” Critical care medicine vol. 30,8 (2002): 1686-92. doi:10.1097/00003246-200208000-00002 CrossRef Pubmed

10. Fick, A. (1870). Ueber die Messung des Blutquantum in den Herzventrikeln. Sb Phys Med Ges Worzburg, 16-17.

11. Grand, Johannes et al. “Serial assessments of cardiac output and mixed venous oxygen saturation in comatose patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.” Critical care (London, England) vol. 27,1 410. 27 Oct. 2023, doi:10.1186/s13054-023-04704-2 CrossRef Pubmed

12. Grand, Johannes et al. “Serial assessments of cardiac output and mixed venous oxygen saturation in comatose patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.” Critical care (London, England) vol. 27,1 410. 27 Oct. 2023, doi:10.1186/s13054-023-04704-2 CrossRef Pubmed

13. Krafft, P et al. “Mixed venous oxygen saturation in critically ill septic shock patients. The role of defined events.” Chest vol. 103,3 (1993): 900-6. doi:10.1378/chest.103.3.900 CrossRef Pubmed

14. Shepherd, Stephen J, and Rupert M Pearse. “Role of central and mixed venous oxygen saturation measurement in perioperative care.” Anesthesiology vol. 111,3 (2009): 649-56. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181af59aa CrossRef Pubmed

15. Sumimoto, T et al. “Mixed venous oxygen saturation as a guide to tissue oxygenation and prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction.” American heart journal vol. 122,1 Pt 1 (1991): 27-33. doi:10.1016/0002-

8703(91)90754-6. CrossRef Pubmed

Copyright Information