Original Article

March 2026, 35:1

First online: 09 March 2026

Original Article

Incidence and In-hospital Outcomes of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI) among STEMI and NSTEMI Patients: A Single Center Retrospective Cohort Study

Billy Joseph David,1 Arvinjay A. Bautista,1 Andre Enrique Valencia,1 Richard Henry Tiongco II,1 Jose Nicholas Cruz1

Main author: Billy Joseph David, billydavidmd@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUNDTimely recognition and revascularization remain critical for optimizing outcomes in acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Current ACS paradigms may overlook cases without ST-segment elevation, delaying revascularization and increasing adverse events. Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI) provides a paradigm shift on ACS by focusing instead on degree of coronary occlusion and infarct size. This study aims to investigate the incidence, clinical profiles, and in-hospital outcomes of OMI in STEMI and NSTEMI patients.

METHODSThis single center retrospective cohort study analyzed ACS patients who underwent coronary angiography from January 2019 to July 2024. OMI was defined by TIMI flow grades (0–2) or TIMI 3 flow with peak troponin levels ≥10,000 ng/L. In-hospital outcomes included major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), cardiovascular (CV) and non-cardiovascular mortality, cardiogenic shock, acute decompensated heart failure, major bleeding, and acute respiratory failure warranting mechanical ventilation.

RESULTSAmong 527 patients, OMI incidence was 30.17%, with STEMI (71%) significantly exceeding NSTEMI (16.7%). The composite MACE was 41.5%, primarily driven by cardiogenic shock (35%) and acute decompensated heart failure (30%). While OMI NSTEMI patients exhibited higher three-vessel disease and prolonged revascularization times compared to OMI STEMI, no significant difference in composite MACE rates was observed between groups (p = 0.648). Independent predictors of in-hospital MACE included chronic kidney disease (p = 0.027) and multi-vessel coronary artery disease (p = 0.004) in OMI STEMI, and higher Killip score (p = 0.001) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) as a revascularization modality (p = 0.007) in OMI NSTEMI.

CONCLUSIONOMI represents a substantial subset of STEMI and NSTEMI patients, underscoring the limitations of traditional ACS classifications. Despite presenting without ST-segment elevation, OMI NSTEMI shares prognostic similarities with OMI STEMI, emphasizing the need for early recognition and intervention to reduce adverse outcomes. Further research with larger cohorts is needed to evaluate long-term clinical outcomes.

KeywordsAcute Coronary Syndrome; Occlusion Myocardial Infarction; STEMI; NSTEMI

INTRODUCTION

Significance of the Study

In acute coronary syndrome (ACS), timely reperfusion through thrombolytic therapy or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is critical to restoring blood flow in cases of acute total or near-total coronary occlusion, thereby preventing irreversible myocardial infarction. In the current paradigm in the American, European and even in the Philippine guidelines, ACS is an umbrella term for different types of myocardial infarction, including unstable angina, Non-ST elevation Myocardial Infarction (NSTEMI), and ST elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI). Particularly, this STEMI vs NSTEMI paradigm was based on different randomized controlled trials during the 1980s and 1990s in which the outcome measured in these trials are that of mortality, rather than angiographic coronary occlusion. However, despite the widespread adoption of this paradigm, studies have shown that NSTEMI patients may present with angiographic coronary occlusion despite not presenting with ST elevation pattern on ECG, and thus, these patients do not receive the timely reperfusion needed to salvage the myocardium. Thus, a new paradigm was introduced by H. Pendell Meyers et al. in which acute coronary syndromes were classified instead into occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) and non-occlusion myocardial infarction (NOMI). Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI) is characterized by an acute culprit lesion with either TIMI 0-2 flow or TIMI 3 flow accompanied by a peak troponin level exceeding 10,000 ng/L.1, 2

Given that not all OMIs manifest as ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and many instead present as non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), this first retrospective study conducted in the Philippines aimed to provide valuable insights for cardiologists and emergency physicians. Specifically, it examined the incidence of OMI among patients presenting with suspected ACS symptoms in the emergency room, despite the absence of ST elevation on their initial ECG. Furthermore, the study explored the clinical profiles and angiographic features of patients who are most likely to present with OMI.

Rationale of the Study

Current clinical guidelines and paradigms often equate ST elevation with acute total or near-total coronary occlusion, which prompts the need for immediate revascularization. However, under the existing STEMI and NSTEMI classifications, approximately 25% to 30% of NSTEMI patients with unrecognized Occlusive Myocardial Infarction (OMI) experience delayed revascularization. This delay contributes to an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including higher in-hospital, short-term, and long-term mortality, compared to patients with Non-Occlusive Myocardial Infarction (NOMI). Conversely, about 15% to 35% of STEMI activations are identified as false positives, where no culprit lesion is found on coronary angiography.1

In response to these diagnostic challenges, H. Pendell Meyers et al. (2020) proposed the OMI/NOMI paradigm, which extends beyond ST elevation to more accurately identify acute coronary occlusions. This study aimed to contribute to the ongoing discourse by evaluating the incidence and clinical implications of OMI in patients presenting with suspected ACS, who may not exhibit ST elevation on their initial ECG.3

Background Information and Literature Review

Recent studies have explored the paradigm of Occlusive Myocardial Infarction (OMI) as an alternative perspective for urgent revascularization, challenging the traditional STEMI/NSTEMI framework. Nevertheless, this replacement paradigm has not been widely embraced, resulting in a scarcity of studies, and none have been conducted so far in the Asian or Philippine regions.

Clinical characteristics of OMI patients

Since NSTEMI patients may present with acute coronary occlusion, which is the usual presentation of STEMI patients, it is important to identify clinical features that may identify OMI patients from NOMI patients. Knoery et al. (2021)4 conducted a

study on patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), revealing significant similarities between OMI in NSTEMI patients and those with STEMI. According to the results of their study, OMI patients present more with ST elevation pattern on ECG, have higher incidence of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest, more elderly and frail patients, but surprisingly has less comorbidities than NOMI. In addition, the study of Abusharekh et al. (2024) also showed that NSTEMI patients with OMI had a higher incidence of cardiogenic shock and no-reflow phenomena compared to their non-occlusive MI (NOMI) counterparts.5 While the clinical characteristics of the OMI and STEMI patients are very similar in the study of Knoerv et al. (2021), it failed to identify distinct characteristics that could distinguish specifically between occlusive and non-occlusion MI.4 In another study by Bruno et al. (2023), they described that even coronary artery involvement and the territories they supply was associate with OMI despite not having any ST elevation on

the ECG. Moreover, they identified predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in OMI patients such as left circumflex (LCx) artery involvement, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, lymphocyte and neutrophil counts.6

ECG Characteristics of OMI patients

Based on the OMI/NOMI paradigm, it is evident that ST elevation alone is not sufficient to detect cases of OMI. Thus, there are several studies which attempted to identify ECG characteristics of OMI patients. In the study of H. Pendell Meyers et al. (2021),1 they aimed to compare the accuracy of ECG interpretation using predefined OMI ECG findings versus STEMI criteria for identification of OMI, and explored ECG findings of OMI cases without STEMI criteria. Some of the ECG findings they found include pathologic Q waves, terminal QRS distortion, hyperacute T waves, reciprocal ST depression and/or T-wave inversion, any ST elevation inferior leads with any ST depression and/or T-wave inversion aVL and ST depression maximal in leads V2-V4. Ultimately, they concluded that OMI ECG findings are superior to STEMI criteria.1

A large 2024 meta-analysis by De Alencar Neto et al., involving 23,704 patients, showed that more than half of individuals with acute coronary occlusion did not present with ST-segment elevation, highlighting major diagnostic limitations in the current STEMI/NSTEMI framework.7 Newer technologies aim to address this gap: Zepeda-Echavarría et al. (2024) demonstrated that a novel precordial mini ECG device could detect subtle ST-segment deviations in 65% of OMI patients with low false positives, enabling earlier revascularization and potentially reducing MACE.2

On the other hand, artificial intelligence (AI) models have been used to detect OMI in ACS patients that are presenting without typical ST elevation. In a recent study by Herman et al. (2023),8 an AI model was developed using 18,616 ECGs from 10,543 patients presenting with suspected ACS. This AI model demonstrated superior accuracy in detecting acute OMI compared to the standard ST elevation criteria.

Clinical Outcomes in patients with TIMI 0 and acute coronary occlusion

As of this writing, there has been no study yet on the clinical outcomes of OMI patients, rather most studies have been on electrocardiographic predictors. However, there are scarce studies on patients with TIMI 0 flow or acute coronary occlusion and its clinical outcomes, but not necessarily of patients that fit in the operational definition of OMI by H. Pendell Meyers et al.1

In the study of Aarts et al. (2023),9 NSTEMI patients with TIMI 0 flow were compared to STEMI patients with TIMI 0 flow. The primary endpoint was long term MACE, which was a composite of all-cause mortality, any myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), urgent target vessel revascularization, or stroke. Based on this study which involved 468 patients, NSTEMI with TIMI 0 flow have similar clinical outcomes with STEMI patients with TIMI 0 flow. Another study by Mohamed et al. (2024)11 showed that NSTEMI patients with coronary occlusion had higher 30-day occurrence of re-infarction, recurrent chest pain and arrhythmias. More so, the mortality rate was noted to be higher in patients with OMI compared with NSTEMI without occlusive MI. These studies show how OMI can affect clinical outcomes despite not presenting as ST elevation in the surface ECG.

OBJECTIVES

The general objective of this study is to compare the incidence and in-hospital outcomes of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI) among STEMI and NSTEMI patients admitted to St. Luke’s Medical Center–Global City from January 1, 2019, to July 31, 2024. Specifically, the study aims to determine the proportion of OMI in both STEMI and NSTEMI groups during the study period; to describe the clinical, electrocardiographic, and angiographic characteristics of patients with OMI; and to compare the in-hospital outcomes between OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI patients. These outcomes include the primary composite major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE)—cardiovascular mortality, non-cardiovascular mortality, acute decompensated heart failure, cardiogenic shock after angiography or PCI, BARC type 3 and 5 bleeding, and acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation—as well as the secondary outcomes analyzing each component individually. Additionally, the study seeks to identify predictors of in-hospital outcomes based on clinical, ECG, and angiographic characteristics among patients with OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI.

METHODS

Type of Study, Time Period and Target Population

A single-center, retrospective cohort study was conducted with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients who underwent coronary angiogram, particularly those with ST-segment myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), between January 1, 2019, to July 31, 2024 at St. Luke’s Medical Center-Global City, Taguig City, Philippines. Baseline characteristics, procedural characteristics, and follow up data were obtained via the hospital’s electronic medical records.

Criteria for Subject Selection

The study included adult patients aged 18 years and older who were admitted to St. Luke’s Medical Center–Global City with a diagnosis of STEMI or NSTEMI and who subsequently underwent coronary angiography. Patients were excluded if they were admitted for unstable angina, were pregnant or breastfeeding, or were found to have chronic total occlusion (CTO) on angiography. Those who arrived in cardiac arrest and were deemed unsuitable for any interventional procedure, as well as patients who had do-not-resuscitate directives and did not consent to intervention, were also excluded from the study.

Description of Study Procedure:

Method of Subject Selection

A retrospective search of coronary angiography results of STEMI and NSTEMI patients done in our institution from January 1, 2019, to July 31, 2024 were conducted. The Heart Institute of St. Luke’s Medical Center- Global City has a census of the STEMI and NSTEMI patients and their respective coronary angiograms and subsequent official reports were reviewed at the Catheterization laboratory electronic records.

Data Gathered

To determine the incidence of occlusion myocardial infarction (%), the number of STEMI and NSTEMI patients were tallied from January 1, 2019 to July 31, 2024. Patients with OMI were gathered based on the definition of the OMI criteria and this study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. In terms of clinical characteristics, data were gathered from the electronic medical records of the hospital, particularly: age, sex, co-morbidities (presence/absence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, coronary artery disease, stroke, chronic kidney disease), family history of coronary artery disease (CAD), Killip Score on arrival (I, II, III, IV), time to revascularization (minutes/hours), length of total hospital stay (days), baseline measurements of the following laboratory parameters [LDL (mg/dL), HDL (mg/dL), HbA1c (%), eGFR (mL/min), and left ventricular ejection fraction (%).

In terms of electrocardiographic characteristics, data were gathered via the electronic medical records. The following features will be tallied for OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI patients: ST elevation, ST depression, T-wave inversion, left bundle branch block, right bundle branch block, AV block (1st degree, 2nd degree, complete heart block), and atrial fibrillation.

The angiographic characteristics were derived from the official angiographic reports and films. The following characteristics will be derived: baseline HS troponin I (ng/L), extent of severe coronary artery disease (1-vessel, 2-vessel, 3-vessel), culprit vessel involved (left main, left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery, right coronary artery, by-pass graft), basal TIMI flow (0, 1, 2, 3), access site (radial or femoral), percutaneous coronary intervention done (drug eluting stent implantation, drug eluting balloon, mechanical thrombectomy, or no percutaneous coronary intervention done).

In-hospital outcomes of both OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI were gathered as well, particularly: incidence of composite MACE and individual MACE (cardiovascular mortality, non-cardiovascular mortality, acute decompensated heart failure, cardiogenic shock, Type 3 and 5 bleeding based on the BARC criteria, and acute respiratory failure warranting mechanical ventilation.

Description of Outcome Measures

The outcomes that were assessed in this study include a primary outcome, which is the incidence of occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) among STEMI and NSTEMI patients who underwent coronary angiogram, which is measured in percentage (number of OMI in STEMI/total number of STEMI), and (number of OMI in NSTEMI/total number of NSTEMI). This outcome is also based on a similar study done by Meyers et al. (2020)1 who also described prevalence of OMI on patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome.

One of the secondary outcomes included the description of the clinical, electrocardiographic, and angiographic characteristics of the OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI patients, in which descriptive statistics were used. These were expressed as frequency (%): (clinical/electrocardiographic/angiographic characteristic/total number of OMI STEMI or OMI NSTEMI) x 100; mean/standard deviation, median/interquartile range were also used as part of the descriptive statistics.

Another secondary outcome that was analyzed are the composite of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) during the hospital admission alone. This is composed of cardiovascular mortality, non-cardiovascular mortality, cardiogenic shock post angiography or PCI, BARC Type 3 and 5 Bleeding, and Acute Respiratory Failure warranting mechanical ventilation post angiogram or PCI. These outcomes were based on the study of Rodriguez-Leor et al. (2021) who also analyzed inhospital outcomes of STEMI patients.11 This will be expressed as frequency (%): (Composite MACE or Individual MACE/total number of OMI STEMI or OMI NSTEMI) x 100; mean/standard deviation, median/interquartile range were also used as part of the descriptive statistics.

Clinical, electrocardiographic and angiographic predictors of composite MACE were determined based on the subgroup of OMI STEMI and OMI NSTEMI patients. These predictors were determined by univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis. Odds ratio was computed, and its precision to be estimated using a 95% confidence interval. These outcomes were based on a study by Djohan et al. (2024), which analyzed clinical predictors and outcomes of ST elevation myocardial infarction in terms of cardiogenic shock.12

Sample Size Estimation

Sample size was calculated based on the estimation of the population proportion of OMI among STEMI and NSTEMI patients assumed to be 23.1%, (Meyers et al. 2020).1 With a maximum allowable error of 3%, and a reliability of 80%, minimum sample size for all STEMI and NSTEMI patients required is 329.

Sample formula based on estimation of the population proportion n = z 2 p (1-p)/e 2 where:

- n = sample size

- z = critical value from standard normal distribution

- p = population proportion

- e = margin of error

Data Analysis

Data were encoded in MS Excel by the researchers. Stata MP version 17 software was used for data processing and analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean/standard deviation (SD) or median/interquartile range (IQR) depending on the data distribution. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of data. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparison of variables between STEMI vs. NSTEMI was performed using Independent t test and Mann Whitney U test for continuous variables, and Chi Square test and Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables.

Firth’s bias-reduced logistic regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of MACE. Separate models were created for STEMI and NSTEMI. Univariable analysis using a p<0.20 criteria were performed to identify variables that will be entered into the multivariable model.13 Model building was done using backward elimination technique. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki (2013), ICH-GCP guidelines (E6 R2) and national ethical rules (NEG HHRR 2017), and received ethics approval from the SLMC Institutional Ethics Review Committee on 25 October 2024. Patient confidentiality was maintained: records were anonymized and coded, only investigators could link codes to

names, and all data were password-protected and stored securely by the principal investigator. Investigators were responsible for data integrity (accuracy, completeness, legibility), and all study documents will be retained confidentially for at least five years before secure destruction.

RESULTS

Incidence of Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI)

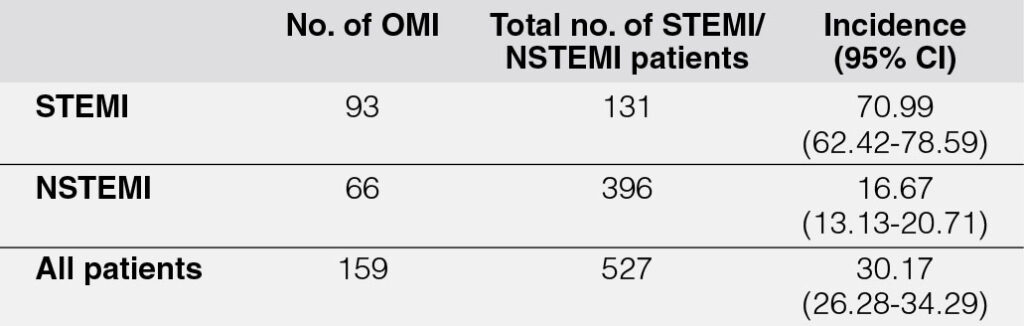

During a five-year period, a total of 527 patients diagnosed with STEMI and NSTEMI were documented. Among these, 396 (75.1%) were NSTEMI cases, while 131 (24.9%) were STEMI cases. Within this cohort, 159 patients met the criteria for Occlusion Myocardial Infarction (OMI)2, corresponding to an overall incidence rate of 30.17% (Table 1). Notably, the incidence of OMI was higher among patients with STEMI compared to those with NSTEMI.

Baseline Characteristics of OMI Patients

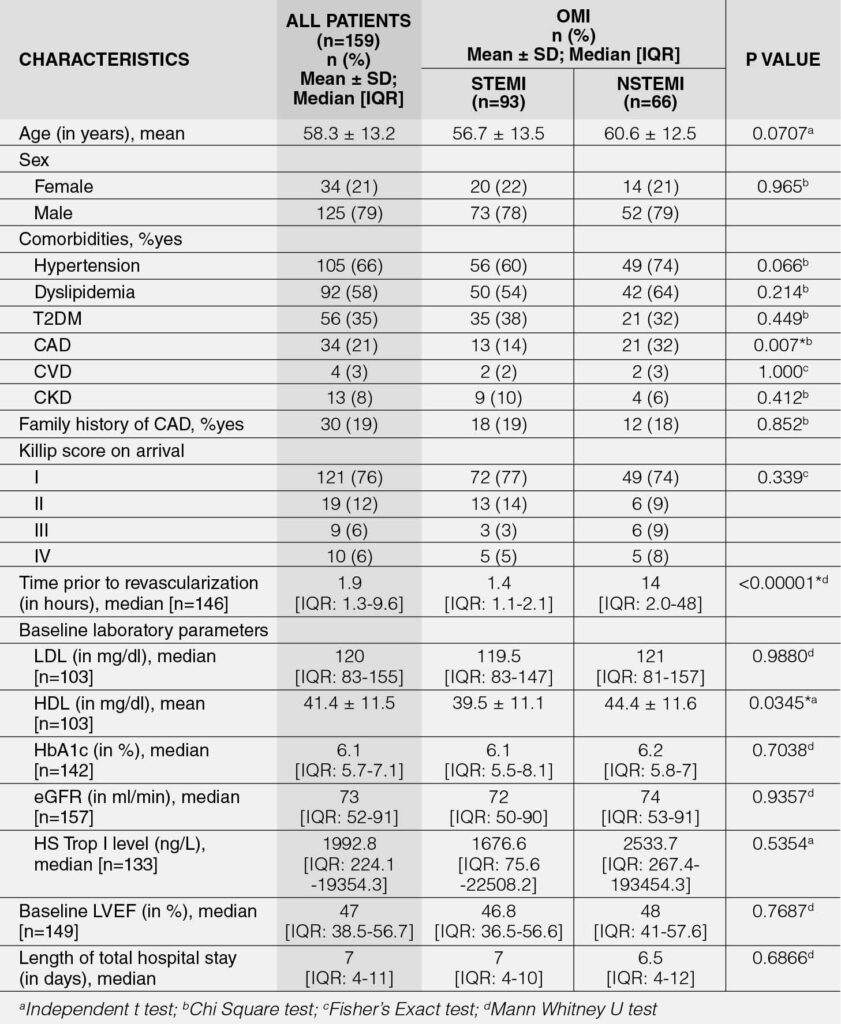

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics of patients with OMI categorized as STEMI and NSTEMI, with a comparison made between the two groups. The mean age of the cohort was 58.3 years, with a predominance of male patients. Hypertension (66%) and dyslipidemia (58%) were the most prevalent comorbidities. The median low-density lipoprotein (LDL) level was 120 mg/dL, the mean high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level was 41.4 mg/dL, and the median glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was 6.1%. Additionally, the median estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 73, and the median left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 47%. The median high sensitivity troponin I (HS Trop I) level was elevated in both groups at 1992.8 ng/L, but did not ultimately reach cut off for troponin for the OMI definition.2 Some patients presented with a normal HS Trop I level of 4.9 ng/L but the highest HS Trop I recorded was 522,252.2 ng/L on initial presentation. However, there was no significant difference between the HS Trop I levels of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI (p=0.5354).

Despite the presence of OMI, only 19% of patients had a significant family history of coronary artery disease, and the majority presented with a Killip class I score upon admission. Among both OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients, the median time to revascularization, whether by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), was 1.9 hours. The median total hospital stay was 7 days for both groups. Survivors (n = 143) had a shorter median hospital stay of 7 days [IQR: 4–10; Range: 2–68 days], whereas non-survivors (n = 16) had a median time to death of 17 days [IQR: 7–30; Range: 3–111 days].

No significant differences were observed between the two groups, except in the following variables: (1) the prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) (p = 0.007), which was higher among OMI NSTEMI patients compared to OMI STEMI patients; (2) the time to revascularization (p < 0.0001), with OMI NSTEMI patients experiencing a significantly longer median time compared to OMI STEMI patients; and (3) high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels (p = 0.0345), where NSTEMI patients had a significantly higher mean HDL compared to OMI STEMI patients.

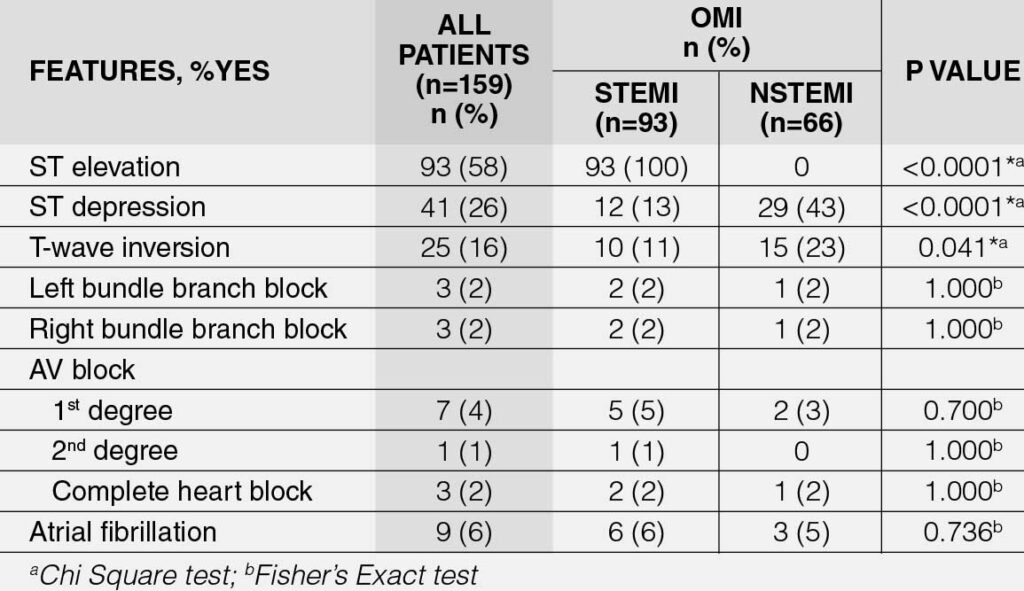

Comparison of ECG Features of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI

Table 3 presents the electrocardiographic (ECG) characteristics of OMI patients, with a comparative analysis between STEMI and NSTEMI subgroups. Notably, 58% of OMI patients exhibit STEMI (p < 0.0001), while a higher proportion of NSTEMI patients present with ST-depression (defined as at least 1 mm ST depression) (p < 0.0001) and T-wave inversion (p = 0.041). However, there is no significant difference in the other ECG features between the two groups.

Comparison of Angiographic Characteristics of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI

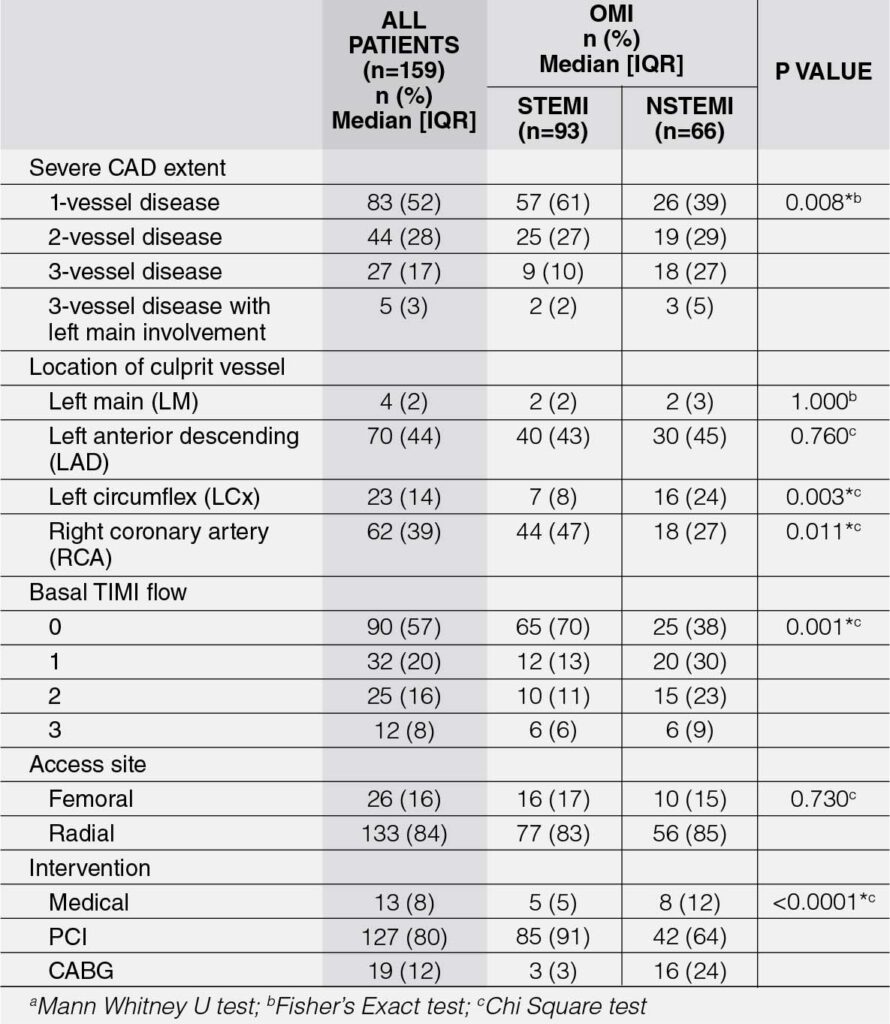

Table 4 shows the angiographic characteristics of OMI patients, and comparison was made between STEMI and NSTEMI. More than half of the OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patient have severe 1-vessel disease and the proportions were significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.008). Further analysis showed that a higher proportion of OMI STEMI patients had only a severe 1-vessel disease compared to OMI NSTEMI patients. Meanwhile, a higher proportion of NSTEMI patients had severe 3-vessel disease than OMI STEMI patients.

The location of the culprit vessel in OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients were located mostly at the left anterior descending artery (LAD) (44%). The left circumflex (LCx) artery as a culprit vessel was significantly higher in OMI NSTEMI than OMI STEMI (p = 0.003). Meanwhile, the right coronary artery (RCA) as the culprit vessel was significantly higher in OMI STEMI than OMI NSTEMI (p = 0.011).

Most OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients had a basal TIMI flow of 0, which corresponds to total coronary occlusion, and the proportions were significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.001). Further analysis showed that a higher proportion of OMI STEMI patients had a TIMI flow of 0 compared to OMI NSTEMI, which presented more with higher TIMI flow scores.

The access site used for coronary angiogram and/or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was mostly radial (84%) and there was no significant difference in terms of access site between the two groups (p = 0.730). In terms of management of OMI, majority underwent PCI (80%). Further analysis showed that a higher proportion of OMI STEMI patients underwent PCI compared to OMI NSTEMI, who on the other hand, had more coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) as a revascularization strategy.

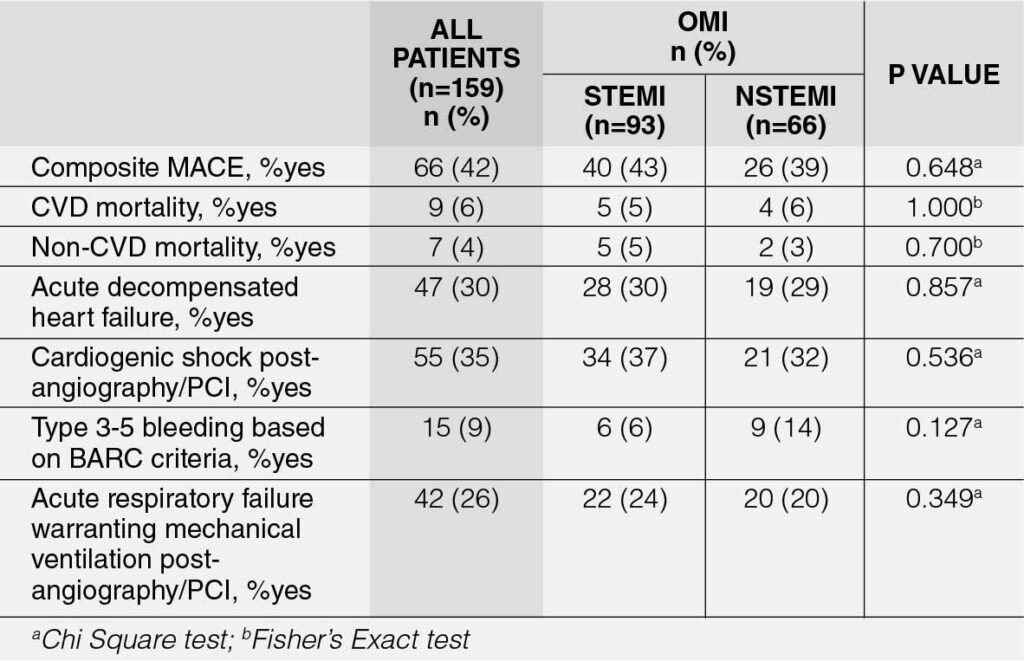

Comparison of In-Hospital Outcomes of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI

Table 5 presents the in-hospital outcomes of OMI patients. The incidence of composite major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was 41.51% (95% CI: 33.76-49.58%). No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of this primary outcome of the study (p = 0.648). Across all individual MACE parameters, the most prevalent was cardiogenic shock (35%), followed by acute decompensated heart failure (30%). No significant difference was detected between the two groups in any of the individual MACE parameters.

Predictors of In-Hospital Clinical Outcomes for OMI STEMI

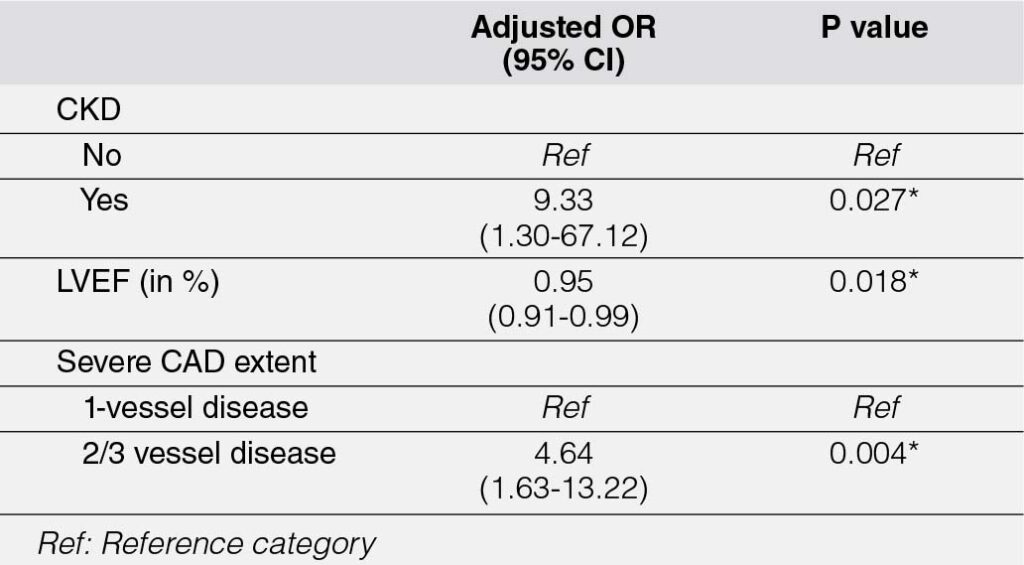

The univariable analysis identified several variables significantly associated with composite major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) among OMI STEMI patients. These included: (1) chronic kidney disease (CKD) (p = 0.023), with patients having an 8-fold higher odds of composite MACE compared to those without CKD; (2) Killip score at arrival (p = 0.024), where patients with a Killip score of II–IV exhibited approximately 4-fold higher odds of composite MACE compared to those with a Killip score of I; (3) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (p = 0.019), where each 1% increase in LVEF was associated with a 5% reduction in the odds of composite MACE; and (4) coronary artery disease (CAD) extent (p = 0.003), with patients having severe 2-vessel or 3-vessel disease demonstrating approximately 4-fold higher odds of composite MACE.

After multivariable analysis (Table 6), three variables remained statistically significant: (1) CKD, which conferred a 9-fold higher risk of composite MACE compared to patients without CKD (p = 0.027); (2) LVEF, with each 1% increase associated with a 5% reduction in the odds of composite MACE (p = 0.018); and (3) CAD extent (p = 0.004), where patients with severe 2-vessel or 3-vessel disease exhibited approximately 5-fold higher odds of composite MACE.

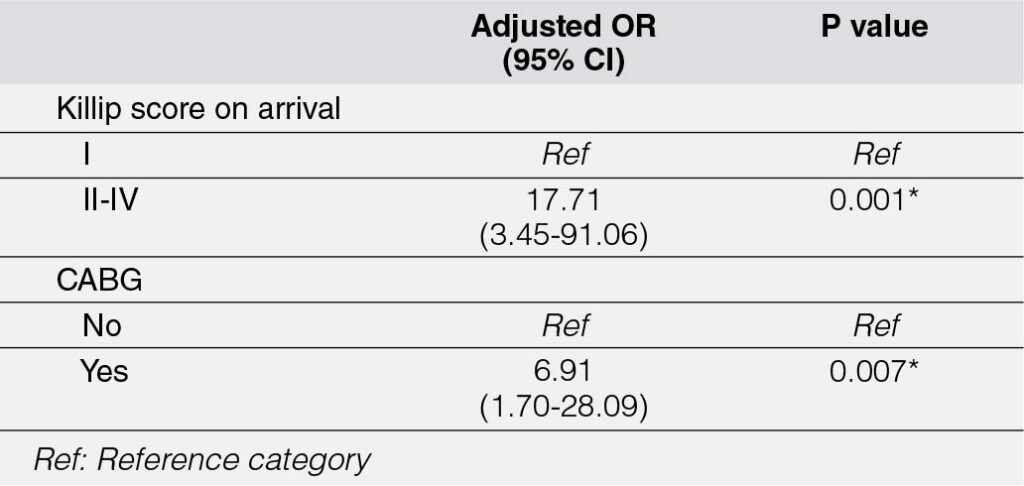

Predictors of In-Hospital Clinical Outcomes for OMI NSTEMI

The univariable analysis identified several variables significantly associated with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) among NSTEMI patients. These include: (1) age (p = 0.024), with a 6% increase in the odds of MACE for every one-year increment in age; (2) Killip score on arrival (p = 0.001), where patients with Killip scores of II–IV had approximately 13-fold higher odds of MACE compared to those with a Killip score of I; (3) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (p = 0.031), which was associated with approximately four-fold lower odds of MACE; and (4) CABG (p = 0.016), where patients who underwent CABG had about 4-fold higher odds of MACE.

In the multivariable analysis (Table 7), only two variables remained statistically significant: (1) Killip score on arrival (p = 0.001), with patients presenting with Killip scores of II–IV demonstrating approximately 18-fold higher odds of MACE compared to those with a Killip score of I, and (2) CABG (p = 0.007), with patients undergoing CABG showing about 7-fold higher odds of MACE.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to document the incidence of occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) based on the definition proposed by H. Pendell- Meyers et al. (2021),1 and Zepeda-Echavarría et al. (2024).2 Over a 5-year period, the overall incidence of OMI was 30.17%, with STEMI patients demonstrating a markedly higher prevalence (71%) compared to NSTEMI patients. These findings stand in contrast to the results of Abusharekh et al. (2024), who reported 2,269 OMI cases over a 15-year timeframe and noted a higher proportion of OMI among NSTEMI patients instead. Notably, 29.3% of NSTEMI cases in their cohort were associated with acute total occlusion (ATO). This discrepancy underscores the potential influence of methodological differences and variations in study populations on the reported incidence of OMI.5

Our study demonstrates that the mean age of patients presenting with OMI was 58.3 years, with a predominance of males. Most of these patients had hypertension and dyslipidemia as underlying comorbidities, while only a small proportion (19%) had pre-existing coronary artery disease (CAD). These findings are consistent with those reported by Zepeda-Echavarría et al. (2024), whose study cohort similarly consisted of patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain or equivalent anginal symptoms who subsequently underwent coronary angiography.2 However, a notable distinction in our study is the identification of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as an independent predictor of in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in OMI STEMI patients, as evidenced by both univariable and multivariable analyses. Similar associations have been reported by Farag et al. (2024), who identified CKD as a risk factor for incomplete revascularization and subsequent MACE, albeit in patients with chronic coronary syndrome (CCS).14

Although only a small percentage of OMI patients in our study had underlying coronary artery disease (CAD), a higher proportion of OMI NSTEMI patients exhibited pre-existing CAD despite having higher low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels. These patients also experienced significantly longer revascularization times compared to OMI STEMI patients. Nevertheless, the median revascularization time for both OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients was 1.9 hours, which remains within the guideline-recommended cutoff for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) STEMI (<2 hours).15 It is important to note that, at the time of this writing, specific revascularization guidelines for OMI are lacking, with existing recommendations limited to the ACS STEMI and NSTEMI framework.

Interestingly, the high-sensitivity troponin I (HS-Trop I) levels in our OMI STEMI and NSTEMI cohorts were below the troponin cutoff (median 1992.8 ng/L) defined for OMI (≥10,000 ng/L). This contrasts with the findings of Zepeda-Echavarria et al. (2024), who reported mean troponin levels of 87,583 ± 106,652 ng/L for OMI STEMI and 5,315 ng/L for OMI NSTEMI. Furthermore, the troponin levels in our OMI cohort were comparable to those reported for non-occlusive myocardial infarction (non-OMI) NSTEMI patients in the same study (1,678 ± 2,574 ng/L).2 However, this discrepancy does not exclude our patients from the OMI definition, as 93% of our OMI STEMI and NSTEMI cases presented with TIMI flow grades of 0–2, a key criterion for OMI. Notably, in our study, troponin levels were not predictive of composite in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in either OMI STEMI or NSTEMI patients, based on univariable and multivariable analyses.

In terms of electrocardiographic (ECG) characteristics, ST-segment elevation was the most common feature, observed in 58% of OMI patients. OMI STEMI patients had a lower prevalence of ST-segment depression and T-wave inversion compared to OMI NSTEMI patients. These findings align with the study by Zepeda-Echavarría et al. (2024), where 82.6% of OMI patients presented with ST-segment elevation, and 79% demonstrated some form of ST-segment deviation.2 However, in our study, ECG characteristics, including ST-segment elevation, did not emerge as predictors of composite in-hospital MACE in univariable or multivariable analyses.

Coronary angiographic findings revealed that more than half of OMI patients had severe single-vessel disease, with a higher proportion among OMI STEMI patients. Conversely, a higher percentage of OMI NSTEMI patients had severe three-vessel disease. In our study, severe two-vessel or three-vessel disease was identified as a significant predictor of in-hospital MACE in OMI STEMI patients. The left anterior descending (LAD) artery was the most common culprit lesion in both OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients, consistent with findings from Zepeda-Echavarría et al. (2024) and Ruivo et al. (2017), who similarly identified the LAD as the most frequent site of a totally occluded infarct-related artery (TO-IRA).2, 16

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was the predominant revascularization strategy among OMI patients in our cohort, with a higher proportion of OMI STEMI patients undergoing PCI. In OMI STEMI, the mode of revascularization was not predictive of in-hospital MACE. However, in OMI NSTEMI, PCI was associated with lower odds of in-hospital MACE, while coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was linked to higher odds of in-hospital MACE in multivariable analyses. This may be attributed to the prolonged revascularization times prior to CABG in OMI NSTEMI patients in our study, potentially leading to worse outcomes compared to PCI.

The overall incidence of composite in-hospital MACE among OMI patients was 41.51%, with no significant difference between OMI STEMI and NSTEMI. Cardiogenic shock and acute decompensated heart failure were the most common MACE, with no significant differences in individual components of in-hospital MACE between OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients. These results are comparable to those reported by Ruivo et al. (2017), who observed higher in-hospital mortality among STEMI patients with TO-IRA compared to NSTEMI patients with or without TO-IRA.16 Conversely, Abusharekh et al. (2024) demonstrated that OMI STEMI was associated with unfavorable procedural outcomes and higher long-term mortality.5 These divergent findings highlight the complexity of OMI pathophysiology and suggest that OMI NSTEMI patients may share prognostic and pathophysiological similarities with OMI STEMI, underscoring the need for urgent revascularization in this population.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the final sample size of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients was relatively small. Although we included all STEMI and NSTEMI patients from January 1, 2019, to July 31, 2024, only 159 patients met the criteria for OMI. This limited sample size posed a constraint on the power of our univariable and multivariable analyses in identifying predictors of in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Consequently, while our study was able to identify potential predictors of MACE for OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients, these findings should be interpreted with caution, especially given the single-center nature of the study.

Second, the retrospective study design and the focus on in-hospital MACE are notable limitations. A prospective study with a larger sample size and an extended follow-up period to evaluate the implications of OMI beyond the in-hospital setting is recommended. Additionally, while our study did not identify any ECG characteristics as predictors of MACE among OMI patients, it is important to note that we analyzed general ECG patterns rather than specific quantitative measurements derived from ECG tracings (e.g., magnitudes of ST elevation or depression, degree of T-wave inversion). Future studies could explore the predictive value of detailed ECG metrics for OMI or validate existing ECG-based models in predicting outcomes among OMI patients.

Despite these limitations, this study provides important insights into the characteristics and outcomes of OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients, contributing to the growing body of literature on this emerging paradigm.

CONCLUSION

This pilot study provides novel insights into the prevalence and clinical outcomes of occlusion myocardial infarction (OMI) in the Philippines. Our findings reveal that approximately one-third of patients presenting with STEMI and NSTEMI exhibit total or near-total occlusion of the epicardial coronary arteries, with the majority of OMI cases occurring in STEMI patients. Notably, there was no significant difference in the incidence of in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) between OMI STEMI and NSTEMI patients. These results underscore the potential limitations of the current acute coronary syndrome framework and highlight the need to reconsider early revascularization strategies for NSTEMI patients with OMI. Further studies involving larger and more diverse populations are essential to validate these findings and refine the management paradigms for OMI.

REFERENCES

1. Meyers, H. Pendell, et al. “Comparison of the ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) Vs. NSTEMI and Occlusion MI (OMI) Vs. NOMI Paradigms of Acute MI.” Journal of Emergency Medicine, vol. 60, no. 3, Mar. 2021, pp. 273–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.10.026. CrossRef Pubmed

2. Zepeda-Echavarria, A., Van De Leur, R. R., Vessies, M., De Vries, N. M., Van Sleuwen, M., Hassink, R. J., Wildbergh, T. X., Van Doorn, J. L., Van Der Zee, R., Doevendans, P. A., Jaspers, J. E. N., & Van Es, R. (2024b). Detection of acute coronary occlusion with a novel mobile electrocardiogram device: a pilot study. European Heart Journal – Digital Health, 5(2), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztae002 CrossRef Pubmed

3. Meyers, H. Pendell, Alexander Bracey, Daniel Lee, Andrew Lichtenheld, Wei J. Li, Daniel D. Singer, Zach Rollins, et al. “Accuracy of OMI ECG Findings Versus STEMI Criteria for Diagnosis of Acute Coronary Occlusion Myocardial Infarction.” IJC Heart & Vasculature, vol. 33, Apr. 2021, p.100767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2021.100767. CrossRef Pubmed

4. Knoery, C., et al. “Identification of the Characteristics of Occlusive Myocardial Infarction: Are There Any Tell-tale Signs?” European Heart Journal, vol. 42, no. Supplement_1, Oct. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab724.1160. CrossRef

5. Abusharekh, Mohammed, et al. “Acute Coronary Occlusion With Vs. Without ST Elevation: Impact on Procedural Outcomes and Long-term All-cause Mortality.” European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, Jan. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcae003. CrossRef Pubmed

6. Bruno, Francesco, et al. “Occlusion of the Infarct-related Coronary Artery Presenting as Acute Coronary Syndrome With and Without ST-elevation: Impact of Inflammation and Outcomes in a Real-world Prospective Cohort.” European Heart Journal – Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes, vol. 9, no. 6, May 2023, pp. 564–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjqcco/qcad027. CrossRef Pubmed

7. De Alencar Neto, José Nunes, et al. “Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy of ST-segment Elevation for Acute Coronary Occlusion.” International Journal of Cardiology, vol. 402, May 2024, p. 131889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.131889. CrossRef Pubmed

8. Herman, R., Meyers, H. P., Smith, S. W., Bertolone, D. T., Leone, A., Bermpeis, K., Viscusi, M. M., Belmonte, M., Demolder, A., Boza, V., Vavrik, B., Kresnakova, V., Iring, A., Martonak, M., Bahyl, J., Kisova, T., Schelfaut, D., Vanderheyden, M., Perl, L., Aslanger E.K., Hatala R., Wojakowski W., Bartunek J., Barbato, E. (2023). International evaluation of an artificial intelligence–powered electrocardiogram model detecting acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal – Digital Health, 5(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztad074 CrossRef Pubmed

9. Aarts, B. R., Groenland, F. T., Elscot, J., Neleman, T., Wilschut, J. M., Kardys, I., Nuis, R., Diletti, R., Daemen, J., Van Mieghem, N. M., & Dekker, W. K. D. (2023). Long-term clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 0 flow. IJC Heart & Vasculature, 48, 101254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2023.101254 CrossRef Pubmed

10. Mohamed, A., Alamein, M., Gammer, F., Elmakki, E., Hamid, E., Gadour, E., Abdelhameed, M., Alamean, M., & Subahi, S. (2024). The outcomes of occlusive vs non-occlusive culprit coronary artery in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS): A descriptive prospective study in a tertiary cardiac centre in Sudan. Clinical Medicine, 24, 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinme.2024.100067 CrossRef

11. Rodriguez-Leor, Oriol, et al. “In-hospital Outcomes of COVID-19 ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients.” EuroIntervention, vol. 16, no. 17, Apr. 2021, pp. 1426–33. https://doi.org/10.4244/eij-d-20-00935 CrossRef Pubmed

12. Djohan, A. H., Evangelista, L. K. M., Chan, K., Lin, W., Adinath, A. A., Kua, J. L., Sim, H. W., Chan, M. Y., Ng, G., Cherian, R., Wong, R. C., Lee, C., Tan, H., Yeo, T., Yip, J., Low, A. F., Sia, C., & Loh, P. H. (2024). Clinical predictors and outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction related cardiogenic shock in the Asian population. IJC Heart & Vasculature, 53, 101463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2024.101463 CrossRef Pubmed

13. Greenland S, Pearce N. Statistical foundations for model-based adjustments. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015 Mar 18;36:89-108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122559. PMID: 25785886. CrossRef Pubmed

14. Farag SI, Mostafa SA, Kabil H, Elfaramawy MR. Chronic kidney disease’s impact on revascularization and subsequent major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with chronic coronary syndrome. Indian Heart J. 2024 Jan-Feb;76(1):22-26. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2023.11.006. Epub 2023 Nov 23. PMID: 38000533; PMCID: PMC10943565. CrossRef Pubmed

15. Robert A Byrne, Xavier Rossello, J J Coughlan, Emanuele Barbato, Colin Berry, Alaide Chieffo, Marc J Claeys, Gheorghe-Andrei Dan, Marc R Dweck, Mary Galbraith, Martine Gilard, Lynne Hinterbuchner, Ewa A Jankowska, Peter Jüni, Takeshi Kimura, Vijay Kunadian, Margret Leosdottir, Roberto Lorusso, Roberto F E Pedretti, Angelos G Rigopoulos, Maria Rubini Gimenez, Holger Thiele, Pascal Vranckx, Sven Wassmann, Nanette Kass Wenger, Borja Ibanez, ESC Scientific Document Group, 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes: Developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), European Heart Journal, Volume 44, Issue 38, 7 October 2023, Pages 3720–3826, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191 CrossRef Pubmed

16. C. Ruivo, L. Graca Santos, F. Montenegro Sa, J. Correia, J. Morais, Portuguese National Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes, P2712 Impact of total occlusions of infarct related artery in patients with acute myocardial infarction without ST elevation on in-hospital mortality: a multicenter analysis, European Heart Journal, Volume 38, Issue suppl_1, August 2017, ehx502.P2712, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx502. P2712 CrossRef

Copyright Information