Case Report

Mar 2023, 32:1

First online: 6 April 2023

Case Report

Device Closure of Aortic Paravalvular Leak

Rajeev Bhardwaj, 1 Sachin Sandhu,2 Shivani Rao3

2 Senior resident, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla 171001. Email: ssachin119@gmail.com

3 Senior resident, Indira Gandhi Medical College, Shimla 171001. Email: shivanirao1109@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Significant paravalvular leak is a serious complication of surgical valve replacement. Approximately 1–5% of PVLs can lead to serious clinical consequences, including congestive heart failure and/or haemolytic anaemia. Surgical intervention was the standard care of treatment for this for years. We describe a case of aortic paravalvular leak, managed with transcatheter closure.

KeywordsParavalvular leak, vascular plug, trans catheter closure

CASE

67 years female underwent double valve replacement in our hospital, for severe mitral regurgitation with severe aortic regurgitation. Bio prosthetic valves were implanted in July 2014. She remained asymptomatic for around 2 years. Now she presented with breathlessness for one and half months. Breathlessness gradually increased. For two weeks, she also had paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea. She also had palpitation, more so on walking, for the last one month. For 10 days, she was having swelling in feet. There was no history of fever or joint pains. She had decreased appetite for two weeks.

On examination, her BP was 130/40 mm HG, pulse 104/min, respiratory rate 28/min. Her JVP was 10cm above the sterna angle with prominent V wave and Y collapse. There was bilateral pitting oedema. First and 2nd heart sounds were normal. There was long early diastolic mummer in left 3rd and 4th intercostal space in parasternal area. There was also short ejection systolic murmur in left upper parasternal area.

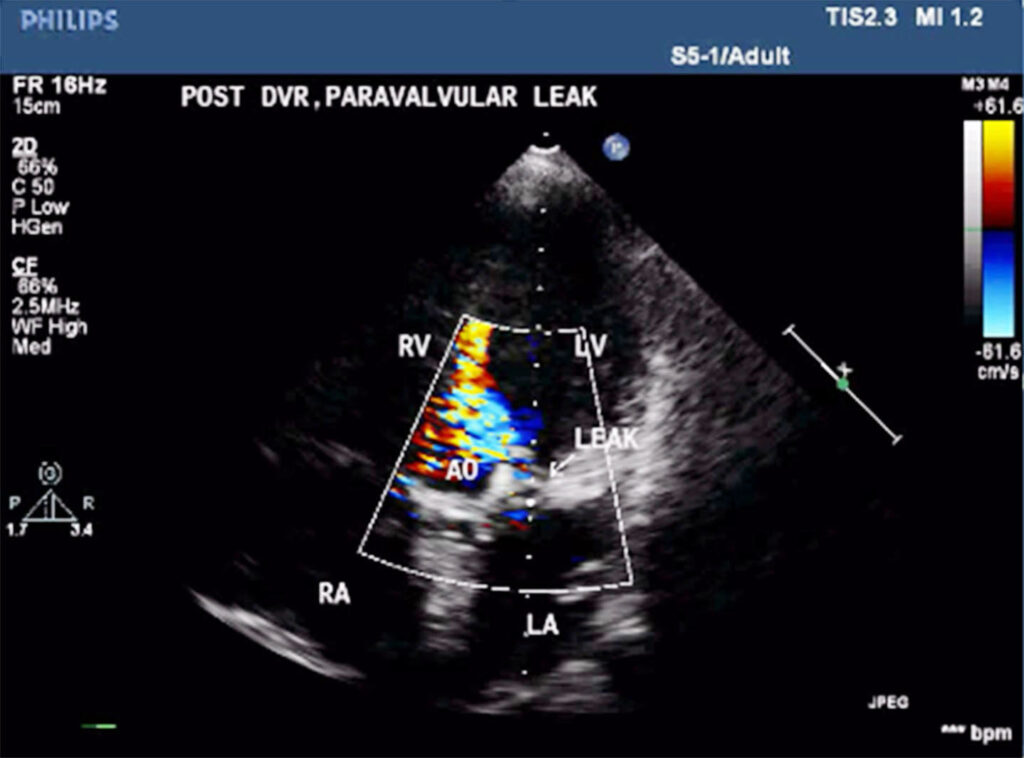

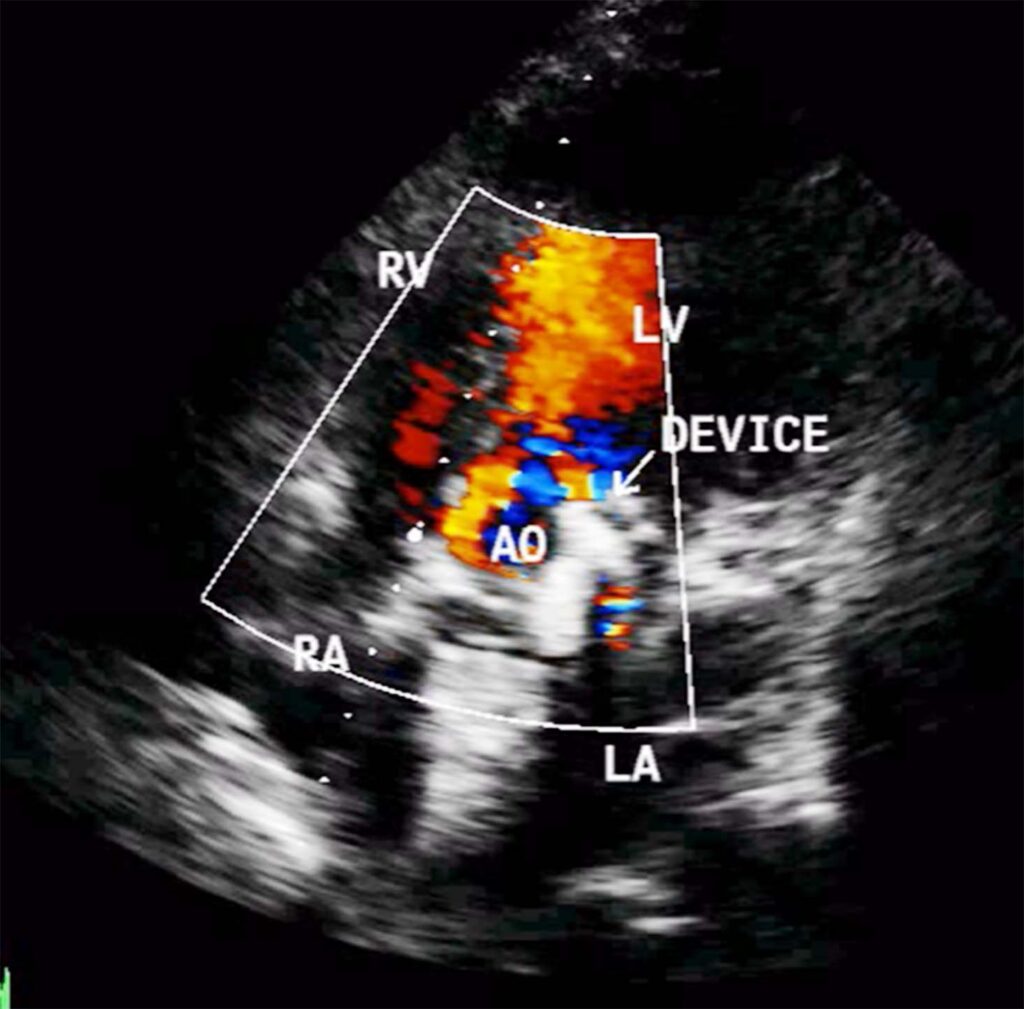

On echocardiography, left ventricle (LV) was enlarged, showed global hypokinesia. There was severe aortic paravalvular leak, posteriorly (Fig 1). Mitral prosthehtetic valve was functioning normally. Ejection fraction was 38%. There was moderate TR, with gradient of 56mm HG.

Laboratory investigations:

HB 10.5gm%

TLC = 6000/mm3

Platelet count = 1.88 lac /mm3

ESR 10 mm in 1st hour

Bilirubin 1.53 mg%

Alkaline phosphtase 96IU.

Haptoblobin 0.14

Reticulocyte count 1.2%

LDH 305 U/L ( Normal < 248)

BUN 22mg%

Creatinine 0.7mg%.

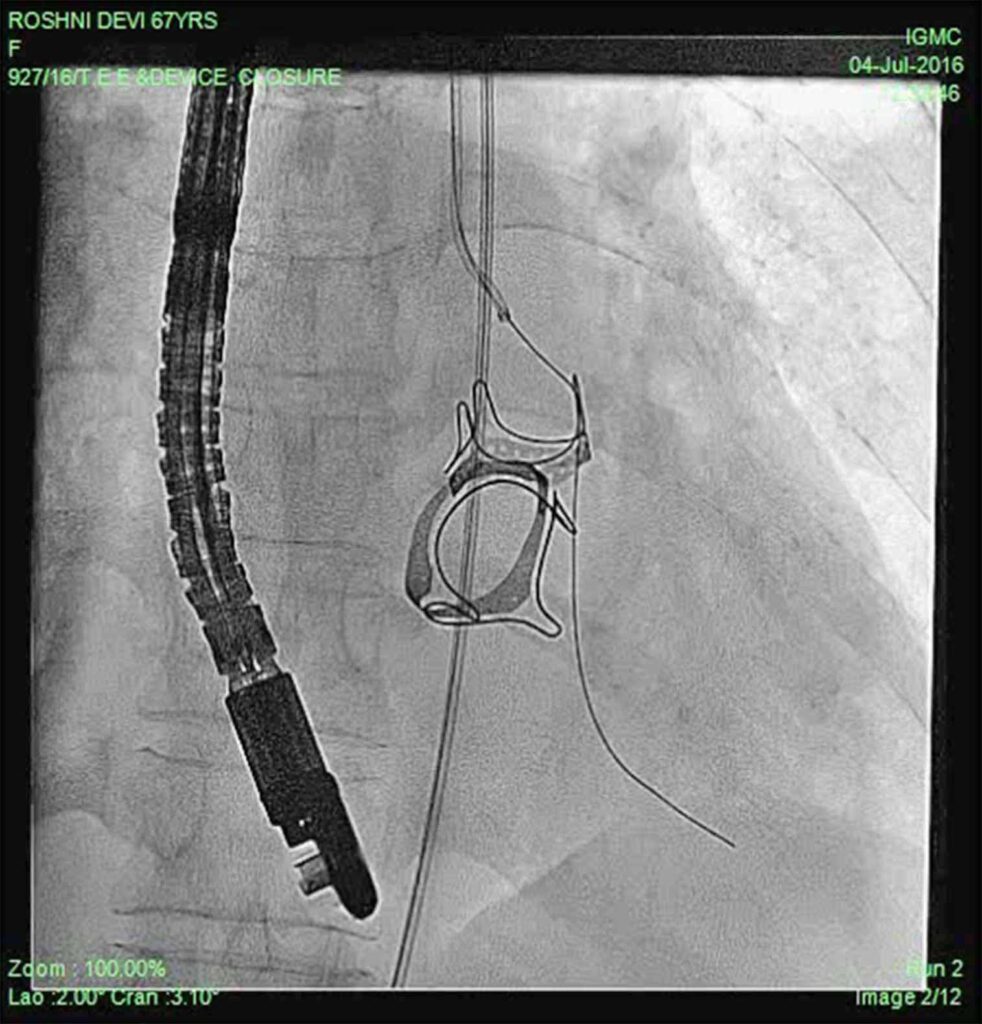

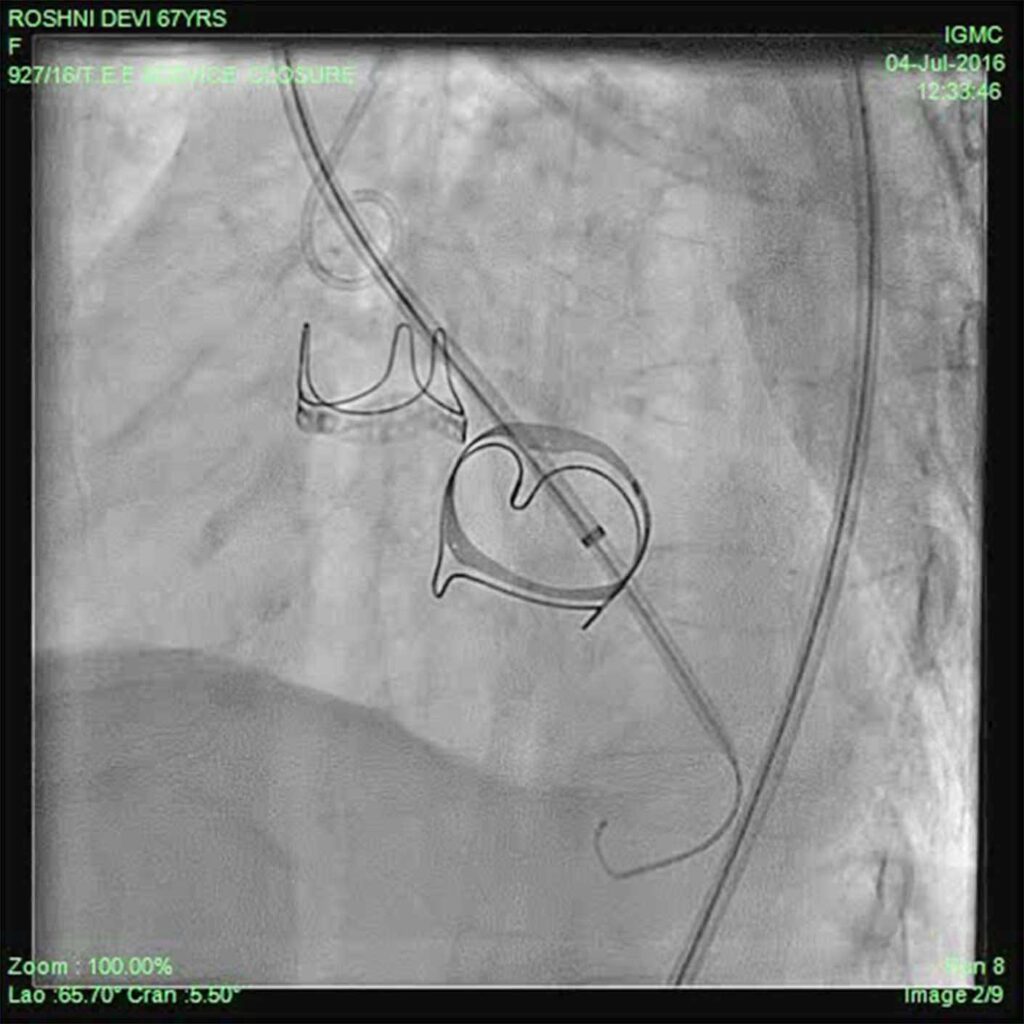

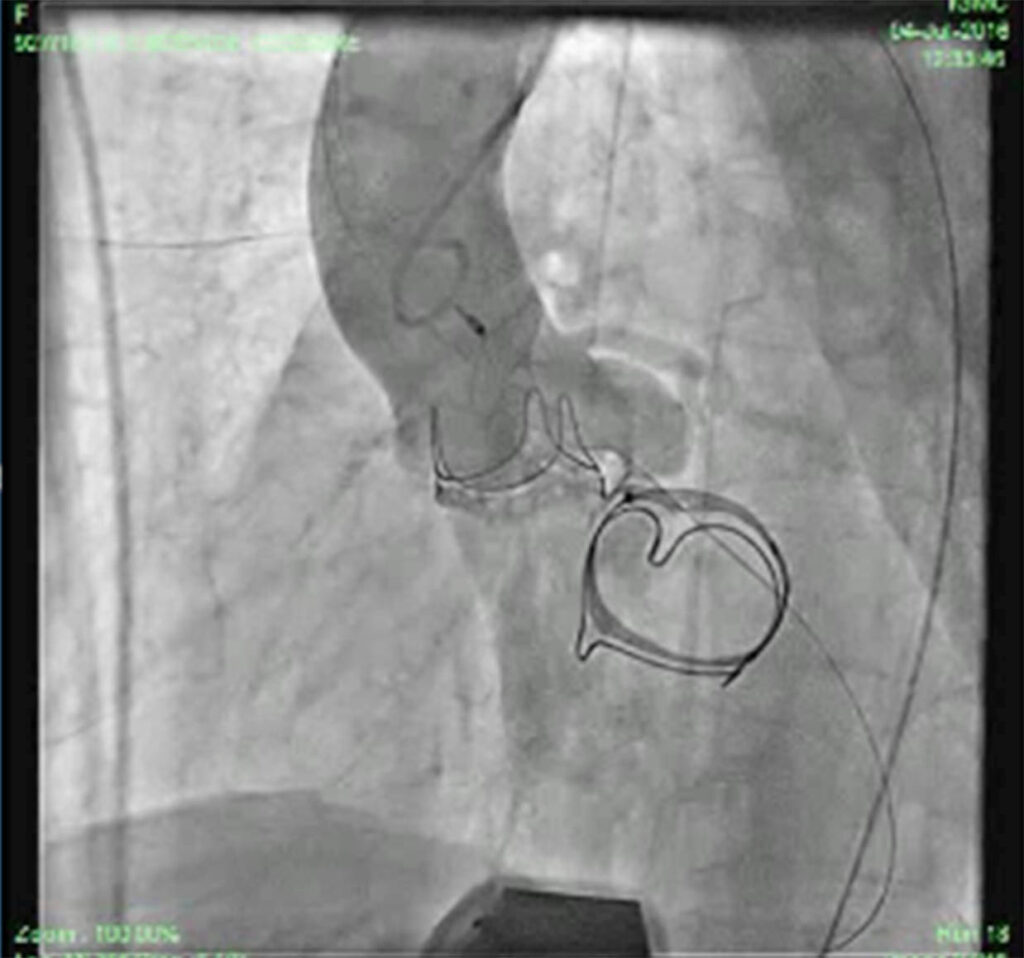

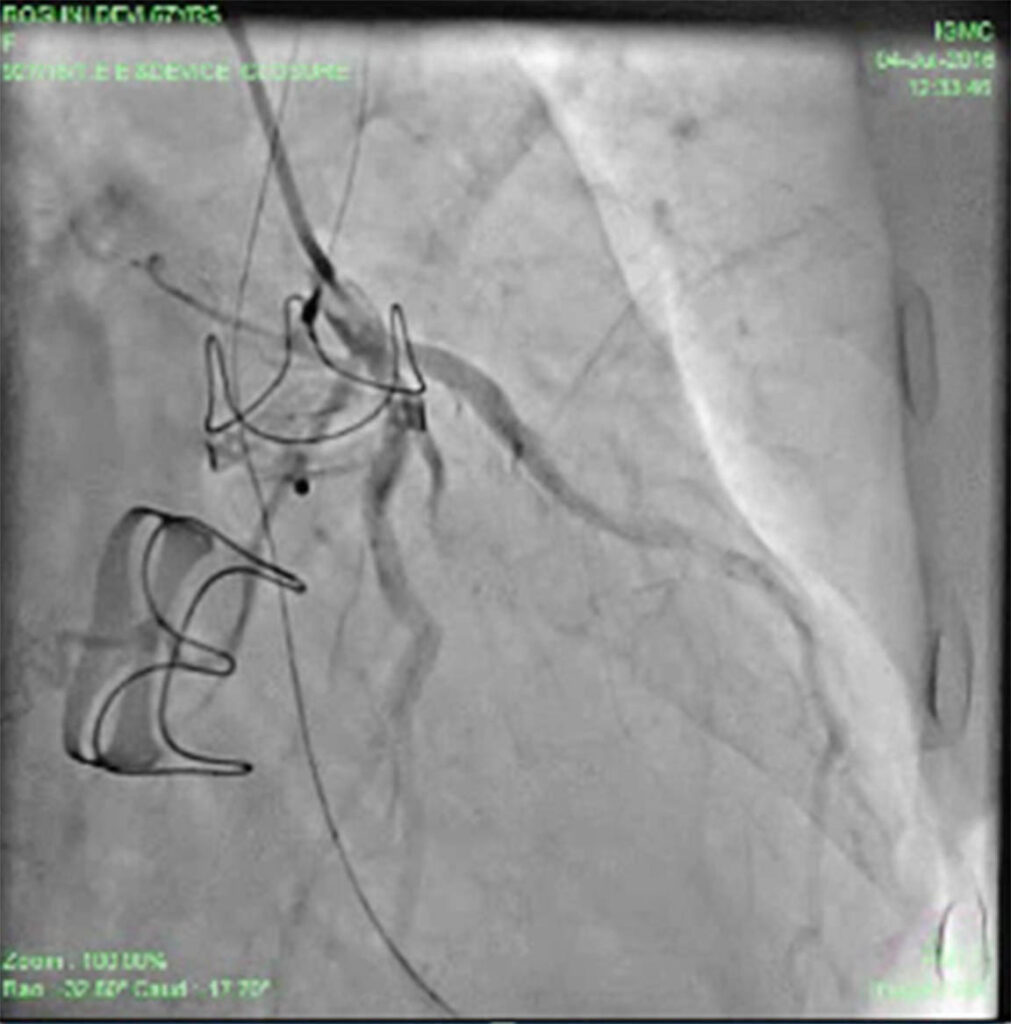

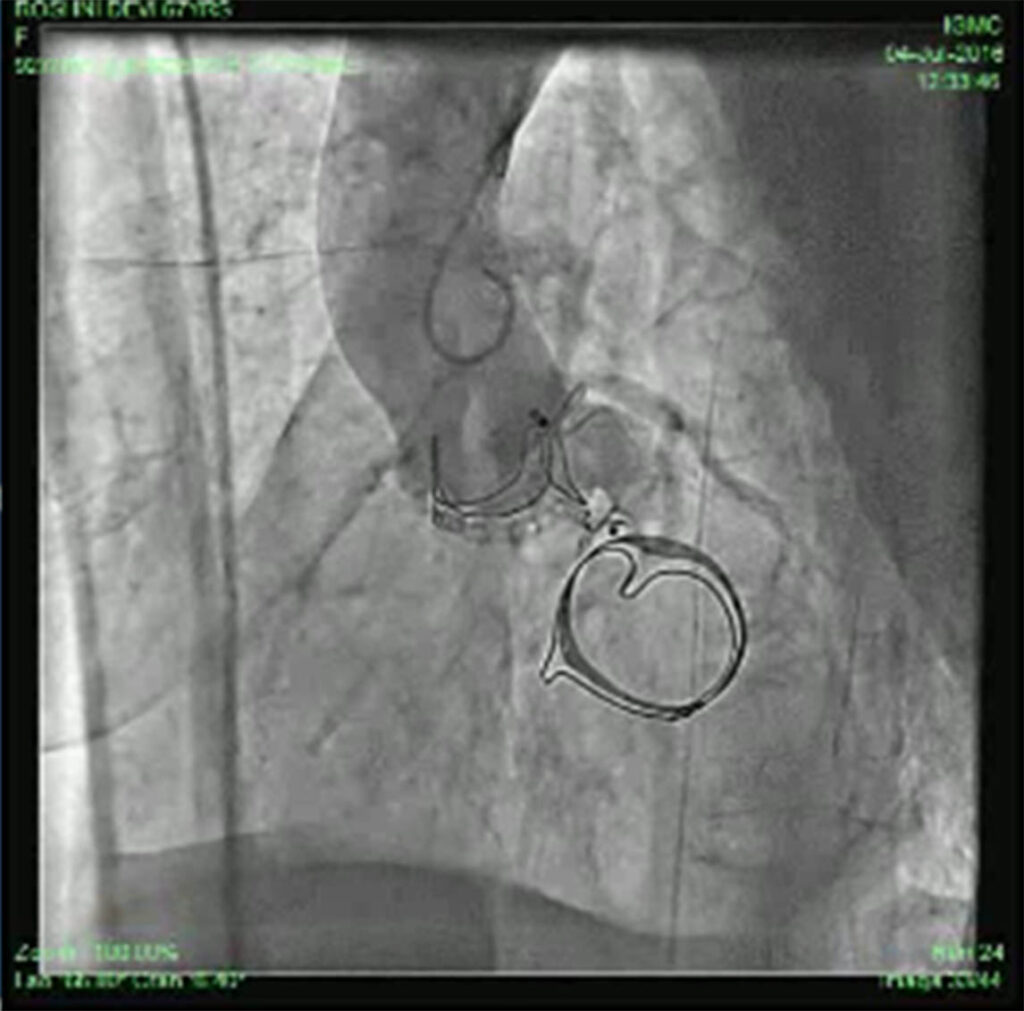

Patient was put on heart failure treatment. She was then taken up for device closure. Aortic root angio was done and it showed filling of LV (Fig 2) through paravalvular leak (PVL). The passage was crossed with 0.018 guidewire with the help of MPA catheter (Fig 3). Then the wire was exchanged to Amplatzer .035, and 10F sheath was negotiated over it into LV (Fig 4). Amplatzer vascular plug (AVP) 12mm was deployed but leak persisted (Fig 5). The device was removed and now 16 mm AVP was implanted. Left coronary angiography was done from trans-radial route (Fig 6), to see that device did not compromise left main coronary artery. There was complete closure of PVL (Fig 7, 8).

DISCUSSION

The incidence of PVLs after surgical valve replacement varies in different studies, ranging from 2–10% in the aortic position and from 7–17% in the mitral position.1-3 Although most PVLs are small, remain asymptomatic and follow a benign clinical course, larger PVLs with serious clinical consequences, such as heart failure, severe haemolytic anaemia or endocarditis, occur in 1–5% of patients who have undergone surgical valve replacement, with most occurring in association with prosthetic mitral valves.2-5 In some cases, PVL diagnosis can be challenging. Often the first signs of suspicion are the presence of an abnormal murmur in the physical examination and the evidence of significant haemolytic anaemia in blood tests. Blood cultures to eliminate endocarditis should be considered. In cases of suspected PVL, patient evaluation must be followed by an echocardiography study to confirm the diagnosis.

For years, surgical re-intervention has been considered the treatment of choice for symptomatic patients with PVLs. It was shown that the overall mortality was lower in the surgical re-intervention group compared with the group treated conservatively.3 However, the operative mortality of surgical treatment of PVL is still high. Transcatheter PVL (TPVL) closure has emerged as a safe, effective and less invasive alternative to surgical re-intervention,6-9 with durable symptom relief in selected patients.7 The retrograde approach is used for closure of most aortic PVLs. The defect is usually crossed using a hydrophilic guide wire over a catheter. After crossing, this guidewire is exchanged for a stiffer wire. Finally, the delivery sheath is advanced and the device is deployed. In some cases an arterio-arterial loop can be established for added support. The closure is mostly done under trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TEE).

We started our procedure under TEE. But shortly after starting the procedure, TEE stopped working. Hence we did our procedure with the help of transthoracic echocardiography. Patient tolerated the procedure well. She improved and was discharged on 4th day. On follow up around 2 years, she is doing well. Her EF after one month was 56%.

REFERENCES

1. Jindani A, Neville EM, Venn G, et al. Paraprosthetic leak: a complication of cardiac valve replacement. J Cardiovasc Surg [Torino]. 1991;32:503–8. Pubmed

2. Ionescu A, Fraser AG, Butchart EG. Prevalence and clinical significance of incidental paraprosthetic valvar regurgitation: a prospective study using transoesophageal echocardiography. Heart. 2003;89:1316–21. CrossRef Pubmed

3. Genoni M, Franzen D, Vogt P, et al. Paravalvular leakage after mitral valve replacement: improved long-term survival with aggressive surgery? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:14–9. CrossRef Pubmed

4. Pate GE, Al Zubaidi A, Chandavimol M, Thompson CR, Munt BI, Webb JG. Percutaneous closure of prosthetic paravalvular leaks: case series and review. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:528–33. CrossRef Pubmed

5. Rallidis LS, Moyssakis IE, Ikonomidis I, Nihoyannopoulos P. Natural history of early aortic paraprosthetic regurgitation: a five-year follow-up. Am Heart J. 1999;138:351–7. CrossRef Pubmed

6. Ruiz CE, Jelnin V, Kronzon I, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous closure of periprosthetic paravalvular leaks. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2210–7. CrossRef Pubmed

7. Sorajja P, Cabalka AK, Hagler DJ, et al. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous repair of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2218–24. CrossRef Pubmed

8. Sorajja P, Cabalka AK, Hagler DJ, et al. Percutaneous repair of paravalvular prosthetic regurgitation: acute and 30-day outcomes in 115 patients. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:314–21. CrossRef Pubmed

9. Millan X, Skaf S, Joseph L, et al. Transcatheter reduction of paravalvular leaks: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:260–9. CrossRef Pubmed

Copyright Information